Anchorite

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (April 2009) |

Anchorite (male)/anchoress (female), (adj. anchoritic; from the Greek ἀναχωρέω anachōreō, signifying "to withdraw", "to depart into the rural countryside"), denotes someone who, for religious reasons, withdraws from secular society so as to be able to lead an intensely prayer-oriented, ascetic and, circumstances permitting, Eucharist-focused life. As a result, anchorites are usually considered to be a type of religious hermit,[1] although there are distinctions in their historical development and theology.

The anchoritic life is one of the earliest forms of Christian monastic living. Popularly it is perhaps best-known from the surviving archeological and literary evidence of its existence in medieval England.

In the Roman Catholic Church today it is one of the "Other Forms of Consecrated Life" and governed by the same norms as the consecrated eremitic life (The Code of Canon Law 1983, canon 603).[2]

Contents |

[edit] Historical development

[edit] In medieval times

The anchoritic life became widespread during the early and high Middle Ages. Examples of the dwellings of anchorites and anchoresses survive. They tended to be a simple cell (also called "anchorhold"), built against one of the walls of the local village church. Once the inhabitant had taken up residence, the bishop permanently bricked up the door in a special ceremony.

Hearing Mass and receiving Holy Communion was possible through a small, shuttered window in the common wall facing the sanctuary, called a "squint" or "hagioscope". There was also a small window facing the outside world, through which the inhabitant would receive food and other necessities and, in turn, could provide spiritual advice and counsel to visitors, as these men and women gained a reputation for wisdom. Some anchoresses, however, by knowing everything that was going on in the village, either by being told or observing it, gained reputations as being particularly prone to gossip[citation needed].

Anchorites never left their cell, ate frugal meals, and spent their days in contemplative prayer. Their bodily waste was managed by means of a chamber pot. [3] An idea of their daily routine can be gleaned from an anchoritic Rule known as Ancrene Riwle.

One very well known medieval anchoress is Julian of Norwich whose writings have left a lasting impression on Christian spirituality. A church in Norfolk, All Saints' Church in King's Lynn, still has its original 12th century Anchorhold, intact and still very much used in the daily worship of the church.

[edit] In Christianity today

[edit] In the Roman Catholic Church

When Pope John Paul II revised The Code of Canon Law in 1983 — incorporating changes brought about by the Second Vatican Council — he laid down in canon 603 the norms for the anchoritic life as a form of consecrated life.[2] Thus anchorites who "devote their life to the praise of God and salvation of the world through a stricter separation from the world, the silence of solitude and assiduous prayer and penance", after making a public profession of the three Evangelical counsels (chastity, poverty and obedience) – confirmed by a vow or other sacred bond – in the hands of their diocesan bishop and while observing their plan of life under his direction, as stipulated in canon 603, are now officially recognised by the Catholic Church as living a consecrated life. Concerning the profession of the Evangelical counsels and vows anchorites are therefore in the same position as those monks and nuns that are members of religious orders.

Canon 603 speaks of the "eremitic or anchoritic life" and thereby indicates that, for Church law purposes, it considers the two terms freely interchangeable; and since Canon law typically does not discuss the theological aspects of the various forms of consecrated life, the theological distinction between the eremitic and anchoritic vocations needs to be deduced from their respective names and different historical development and, under the direction of the bishop, validly re-interpreted in the individual anchorite's own circumstances.

At the beginning of the 21st century, the anchoritic life as a distinct vocation has not yet undergone a revival to the same extent as the consecrated eremitic life.

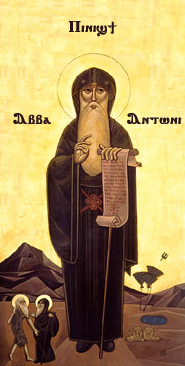

[edit] Notable Anchorites

[edit] See also

- Hermit

- Cenobitic

- Christian monasticism

- Consecrated life

- Book of the First Monks

- Shugendō

- Sokushinbutsu

- Sadhu

[edit] Notes

- ^ BBB Radio 4: Making History – Anchorites

- ^ a b The Code of Canon Law 1983, canon 603

- ^ The Anchoress on line . Q&As Accessed October 2008

[edit] External links

- Historical development

- The Anchorhold at All Saints Church, King's Lynn, Norfolk

- Chapter 1 of The Rule of Saint Benedict re: Anchorites

- The History of Mount Athos During the Byzantine Age

- The Way of an Anchoress

- The Case for an Anchorhold at the Church of St Mary & All Saints in Willingham, Cambridgeshire

- Anchorite Cell at St Luke's Church in Duston

- Marsha, Anchoritic Spirituality in Medieval England: The Form, the Substance, the Rule

- Rotha Mary Clay, Full Text plus illustrations, The Hermits and Anchorites of England.

- Rotha Mary Clay, The Hermits and Anchorites of England, Chapter VII: Anchorites in Church and Cloister

- Note on the Ancrene Riwle

- Select reading list

- Ancrene Wisse ("eets e-editions")

- Ancrene Wisse, Introduction

- anchorite?

- In the Roman Catholic Church today

- Text of canon 603 of The Code of Canon Law (1983, Latin edition) re: Anchorites as members of the Consecrated Life in the Catholic Church

- Text of canon 603 of The Code of Canon Law (1983, English translation) re: Anchorites as members of the Consecrated Life in the Catholic Church

- Immaculate Heart of Mary's Hermitage