eMedicine Specialties > Dermatology > Connective Tissue Diseases

Dermatomyositis

Updated: Apr 13, 2009

Introduction

Background

Dermatomyositis (DM) is an idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM) with characteristic cutaneous findings. Dermatomyositis is a systemic disorder that frequently affects the joints, the esophagus, the lungs, and, less commonly, the heart.1,2

In 1975, Bohan and Peter3 first suggested a set of criteria to aid in diagnosing and classifying dermatomyositis and polymyositis (PM). Of the 5 criteria, 4 relate to the muscle disease; these include progressive proximal symmetrical weakness, elevated muscle enzyme levels, abnormal findings on electromyograms, and abnormal findings from muscle biopsy. The fifth criterion is compatible cutaneous disease.

Bohan and Peter suggested 5 subsets of myositis: dermatomyositis, polymyositis, myositis with cancer, childhood dermatomyositis/polymyositis, and myositis overlapping with another collagen vascular disorder. In a subsequent publication, Bohan and Peter4 noted that cutaneous disease might precede the development of the myopathy; however, only recently was another possible subset of patients with disease that affects only the skin recognized; this condition is known as amyopathic dermatomyositis (ADM), or dermatomyositis sine myositis. The association between dermatomyositis (and possibly polymyositis) and cancer has long been recognized.5,6,7,8

Dermatomyositis sine myositis, also known as amyopathic dermatomyositis, is diagnosed in patients with typical cutaneous disease in whom no evidence of muscle weakness exists and in whom serum muscle enzyme levels are repeatedly normal for a 2-year period in the absence of disease-modifying therapies such as corticosteroids, immunosuppressive agents, or both. When studied, some patients with amyopathic dermatomyositis have abnormal ultrasound, MRI or magnetic resonance spectroscopy, or muscle biopsy findings. These patients have muscle involvement, and their condition may be better classified as hypomyopathic dermatomyositis. Patients with these variations may also reflect an underlying malignancy, and some develop severe pulmonary disease, particularly persons from Asian countries.

Patients exist in whom myositis resolves following therapy but whose skin disease remains as an active, important feature of the disease. These patients are not classified as having amyopathic dermatomyositis, despite the fact that, at this point in time, the skin is the major and often only manifestation of the disease. Sontheimer9 has suggested the term postmyopathic dermatomyositis for these patients.

Rare cutaneous manifestations include vesiculobullous, erosive lesions, and an exfoliative erythroderma. Biopsy samples from patients reveal an interface dermatitis similar to that of biopsy samples of heliotrope rash, Gottron papules, poikiloderma, or scalp lesions. These cutaneous manifestations may be more common in patients with an associated malignancy than in those without a malignancy.

Also see the eMedicine Rheumatology article Dermatomyositis and the Neurology article Dermatomyositis/Polymyositis.

Pathophysiology

Studies of the pathogenesis of the myopathy have demonstrated that the myopathy in dermatomyositis and polymyositis are pathogenetically different.10 Dermatomyositis-associated myopathy appears to be due to vascular inflammation. The pathogenesis of the cutaneous disease is poorly understood, but it is believed that similarities exist with that of cutaneous lupus erythematosus, in which T-cells are involved and antibody-mediated cell cytotoxicity plays a role.

Frequency

United States

The estimated incidence of dermatomyositis/polymyositis is 5.5 cases per million population. However, the incidence appears to be increasing.

Mortality/Morbidity

Dermatomyositis may cause death because of muscle weakness or cardiopulmonary involvement. Patients with an associated cancer may die from the malignancy. Most patients with dermatomyositis survive, in which case they may develop residual weakness and disability. In children with severe disease, contractures can develop if they do not receive physical therapy. Calcinosis may be a complication, particularly in children.

Race

Whites are more frequently affected. However, the rise in the incidence in African Americans is greater than that in whites.

Sex

Women are affected twice as often as men.

Age

Dermatomyositis can occur in persons of any age, but the most common age at onset is in the fifth and sixth decades of life.

Clinical

History

- Patients often present with skin disease as one of the initial manifestations. In as many as 40% of patients, the skin disease may be the sole manifestation at the onset. Muscle disease may occur concurrently, it may precede the skin disease, or it may follow the skin disease by weeks to years.

- Patients often notice an eruption on exposed surfaces. The disease is often pruritic, and, sometimes, intense pruritus may disturb sleep patterns. Patients may also complain of a scaly scalp or diffuse hair loss11 (see Media File 5).

- Muscle involvement manifests as proximal muscle weakness. Patients often begin to note fatigue of their muscles or weakness when climbing stairs, walking, rising from a sitting position, combing their hair, or reaching for items in cabinets that are above their shoulders. Muscle tenderness may occur, but it is not a regular feature of the disease.

- Systemic manifestations may occur; therefore, a review of systems should assess for the presence of arthralgias, arthritis, dyspnea, dysphagia, arrhythmias, and dysphonia.

- Malignancy is possible in any patient with dermatomyositis, but it is much more common in adults older than 60 years. Only a handful of children with dermatomyositis and malignancy have been reported. The history should include a thorough review of systems, as well as an assessment for previous malignancy.

- Children with dermatomyositis may have an insidious onset that hides the true diagnosis until the dermatologic disease is clearly observed and diagnosed. Calcinosis is a complication of juvenile dermatomyositis, but it is rarely observed at the onset of disease. African Americans and patients in lower socioeconomic groups are more likely to have a delay in their diagnosis. The prognosis in children with dermatomyositis is worse in those in whom diagnosis is delayed.

- Several reports describe drug-induced dermatomyositis or existing dermatomyositis exacerbated by certain drugs, including statins and interferon therapy,

Physical

Dermatomyositis is a disease that primarily affects the skin and the muscles, but it might also affect other organ systems.

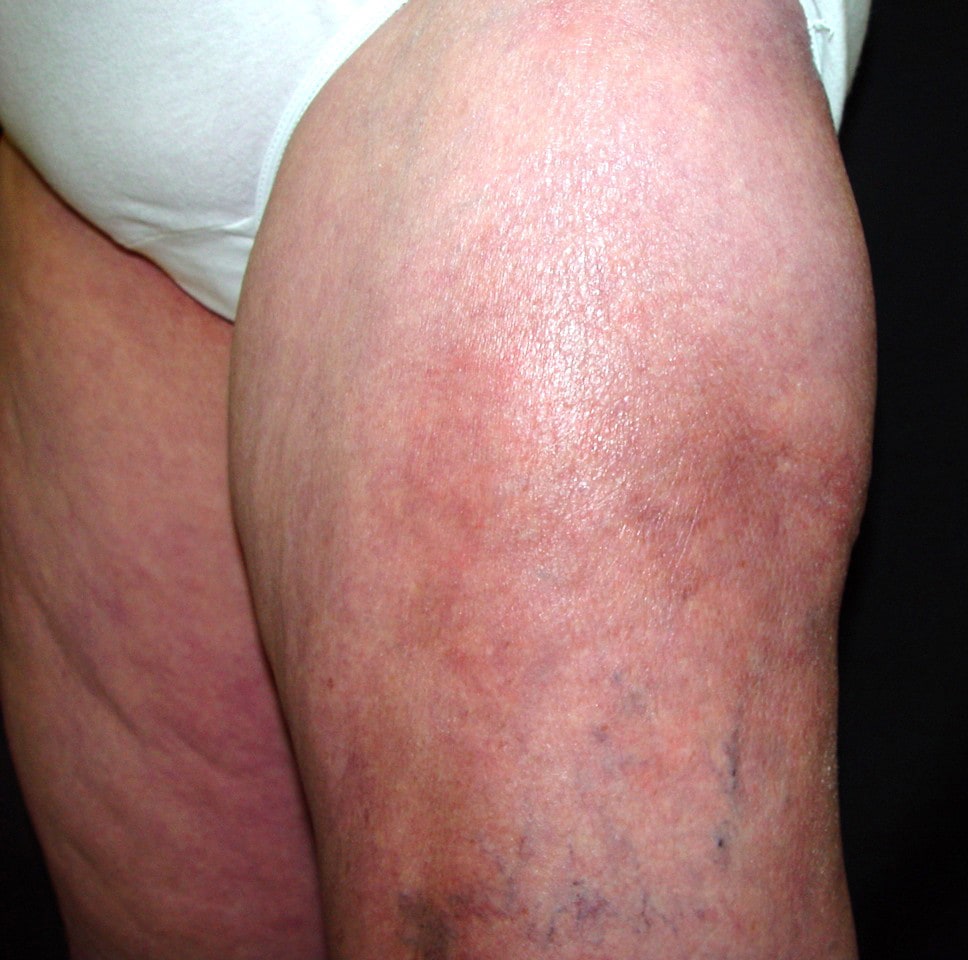

- The characteristic and possibly pathognomonic cutaneous features of dermatomyositis are the heliotrope rash and Gottron papules (see Media File 2). Several other cutaneous features are characteristic of the disease despite not being pathognomonic. They include malar erythema, poikiloderma in a photosensitive distribution, violaceous erythema on the extensor surfaces, and periungual and cuticular changes.

- The heliotrope rash consists of a violaceous to dusky erythematous rash with or without edema in a symmetrical distribution involving the periorbital skin. Sometimes, this sign is subtle and may consist of only a mild discoloration along the eyelid margin. Similar to other areas, scale may be present on the eyelids. A heliotrope rash is rarely observed in other disorders; therefore, its presence is highly suggestive of dermatomyositis.

- Gottron papules are found over bony prominences, particularly the metacarpophalangeal joints, the proximal interphalangeal joints, and/or the distal interphalangeal joints. They may also be found overlying the elbows, the knees, and/or the feet. The lesions consist of slightly elevated, violaceous papules and plaques. A slight scale may be present, and, occasionally, a thick psoriasiform scale is observed. These lesions may resemble lesions of lupus erythematosus, psoriasis, or lichen planus (LP).

- Nail fold changes consist of periungual telangiectases and/or a characteristic cuticular change with hypertrophy of the cuticle and small, hemorrhagic infarcts in this hypertrophic area (see Media File 3). Periungual telangiectases may be clinically apparent, or they may be appreciated only by capillary microscopy.

- Poikiloderma may occur on exposed skin, such as the extensor surfaces of the arm, the V of the neck (see Media File 6), or the upper part of the back (Shawl sign).

- With the exception of the heliotrope rash, the eruption of dermatomyositis is photodistributed and photoexacerbated. Patients rarely complain of photosensitivity, despite the prominent photodistribution of the rash.

- Facial erythema may also occur in dermatomyositis. This change must be differentiated from lupus erythematosus, rosacea, seborrheic dermatitis, or atopic dermatitis. A study from Japan highlighted the finding of disease on the face that mimicked seborrhea.12

- Scalp involvement in dermatomyositis is relatively common and manifests as an erythematous to violaceous, psoriasiform dermatitis. Clinical distinction from seborrheic dermatitis or psoriasis is occasionally difficult. In some patients, nonscarring alopecia may occur and often follows a flare of systemic disease.

- Other cutaneous lesions have been described in patients with dermatomyositis or polymyositis that do not reflect the interface changes observed at histopathologic examination with pathognomonic or characteristic lesions. These include panniculitis (see Media File 9) and urticaria, as well as changes of hyperkeratosis of the palms known as mechanic's hands. Other findings include cutaneous mucinosis, follicular hyperkeratosis, hyperpigmentation, ichthyosis, white plaques on the buccal mucosa, cutaneous vasculitis, and a flagellate erythema.

- Calcinosis of the skin or the muscle is unusual in adults, but it may occur in as many as 40% of children or adolescents with dermatomyositis. Calcinosis cutis manifests as firm, yellow or flesh-colored nodules, often over bony prominences. Occasionally, these nodules can extrude through the surface of the skin, in which case, secondary infection may occur.13

- Muscle findings include weakness and, sometimes, tenderness.

- Muscle disease manifests as a proximal symmetrical muscle weakness. Patients may have difficulty rising from a chair or squatting and then raising themselves from this position. Sometimes, in an effort to rise, patients use other muscles that are not as affected. The careful examiner may note this finding.

- Testing of the muscle strength is part of each assessment of the patient. Often, the extensor muscles of the arms are more affected than the flexor muscles.

- Distal strength is almost always maintained. Muscle tenderness is a variable finding.

- Other systemic features include joint swelling, changes associated with Raynaud phenomenon, and abnormal findings on cardiopulmonary examination.

- Joint swelling occurs in some patients with dermatomyositis. The small joints of the hands are the most frequently involved. The arthritis associated with dermatomyositis is nondeforming.

- Patients with pulmonary disease may have abnormal breath sounds.

- Patients with an associated malignancy may have physical findings relevant to the affected organs.

Causes

- The cause of dermatomyositis is unknown. Factors that have been implicated are listed below.

- A genetic predisposition may exist. Rarely, dermatomyositis manifests in multiple family members. However, a link to certain HLA types may exist. Polymorphisms of tumor necrosis factor may be involved; specifically, the presence of the -308A allele is linked to photosensitivity in adults and calcinosis in children.13,14,15

- Immunologic abnormalities are common in patients with dermatomyositis. Patients frequently have circulating autoantibodies. Abnormal T-cell activity may be involved in the pathogenesis of both the skin disease and the muscle disease. In addition, family members may manifest other diseases associated with autoimmunity.

- Infectious agents, including viruses (particularly coxsackievirus, echovirus, human T-lymphotropic virus 1 [HTLV-1], and human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]), Toxoplasma species, and Borrelia species, have been suggested as possible triggers of the disease.

- Several cases of drug-induced disease have been reported. dermatomyositis-like skin changes have been reported with hydroxyurea in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia or essential thrombocytosis.16,17 Other agents that may trigger the disease include penicillamine, statin drugs, quinidine, and phenylbutazone.

- Dermatomyositis may be initiated or exacerbated by silicon breast implants or collagen injections. However, this evidence is anecdotal and has not been verified in case-control studies.

More on Dermatomyositis |

Overview: Dermatomyositis Overview: Dermatomyositis |

| Differential Diagnoses & Workup: Dermatomyositis |

| Treatment & Medication: Dermatomyositis |

| Follow-up: Dermatomyositis |

| Multimedia: Dermatomyositis |

| References |

| Next Page » |

References

-

Callen JP. Dermatomyositis. Lancet. Jan 1 2000;355(9197):53-7. [Medline].

-

Callen JP, Wortmann RL. Dermatomyositis. Clin Dermatol. Sep-Oct 2006;24(5):363-73. [Medline].

-

Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. Feb 13 1975;292(7):344-7. [Medline].

-

Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (second of two parts). N Engl J Med. Feb 20 1975;292(8):403-7. [Medline].

-

Airio A, Pukkala E, Isomäki H. Elevated cancer incidence in patients with dermatomyositis: a population based study. J Rheumatol. Jul 1995;22(7):1300-3. [Medline].

-

Chow WH, Gridley G, Mellemkjaer L, McLaughlin JK, Olsen JH, Fraumeni JF Jr. Cancer risk following polymyositis and dermatomyositis: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark. Cancer Causes Control. Jan 1995;6(1):9-13. [Medline].

-

Hill CL, Zhang Y, Sigurgeirsson B, et al. Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population-based study. Lancet. Jan 13 2001;357(9250):96-100. [Medline].

-

Sigurgeirsson B, Lindelof B, Edhag O, Allander E. Risk of cancer in patients with dermatomyositis or polymyositis. A population-based study. N Engl J Med. Feb 6 1992;326(6):363-7. [Medline].

-

Sontheimer RD. Skin manifestations of systemic autoimmune connective tissue disease: diagnostics and therapeutics. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. Jun 2004;18(3):429-62. [Medline].

-

Dalakas MC. Molecular immunology and genetics of inflammatory muscle diseases. Arch Neurol. Dec 1998;55(12):1509-12. [Medline].

-

Kasteler JS, Callen JP. Scalp involvement in dermatomyositis. Often overlooked or misdiagnosed. JAMA. Dec 28 1994;272(24):1939-41. [Medline].

-

Okiyama N, Kohsaka H, Ueda N, et al. Seborrheic area erythema as a common skin manifestation in Japanese patients with dermatomyositis. Dermatology. 2008;217(4):374-7. [Medline].

-

Pachman LM, Veis A, Stock S, et al. Composition of calcifications in children with juvenile dermatomyositis: association with chronic cutaneous inflammation. Arthritis Rheum. Oct 2006;54(10):3345-50. [Medline].

-

Lutz J, Huwiler KG, Fedczyna T, et al. Increased plasma thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) levels are associated with the TNF alpha-308A allele in children with juvenile dermatomyositis. Clin Immunol. Jun 2002;103(3 Pt 1):260-3. [Medline].

-

Werth VP, Callen JP, Ang G, Sullivan KE. Associations of tumor necrosis factor alpha and HLA polymorphisms with adult dermatomyositis: implications for a unique pathogenesis. J Invest Dermatol. Sep 2002;119(3):617-20. [Medline].

-

Daoud MS, Gibson LE, Pittelkow MR. Hydroxyurea dermopathy: a unique lichenoid eruption complicating long-term therapy with hydroxyurea. J Am Acad Dermatol. Feb 1997;36(2 Pt 1):178-82. [Medline].

-

Noel B. Lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune diseases related to statin therapy: a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. Jan 2007;21(1):17-24. [Medline].

-

Whitmore SE, Rosenshein NB, Provost TT. Ovarian cancer in patients with dermatomyositis. Medicine (Baltimore). May 1994;73(3):153-60. [Medline].

-

Callen JP. The value of malignancy evaluation in patients with dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. Feb 1982;6(2):253-9. [Medline].

-

Smith ES, Hallman JR, DeLuca AM, Goldenberg G, Jorizzo JL, Sangueza OP. Dermatomyositis: a clinicopathological study of 40 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. Feb 2009;31(1):61-7. [Medline].

-

Ang GC, Werth VP. Combination antimalarials in the treatment of cutaneous dermatomyositis: a retrospective study. Arch Dermatol. Jul 2005;141(7):855-9. [Medline].

-

[Best Evidence] Choy EH, Hoogendijk JE, Lecky B, Winer JB. Immunosuppressant and immunomodulatory treatment for dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Jul 20 2005;CD003643. [Medline].

-

Edge JC, Outland JD, Dempsey JR, Callen JP. Mycophenolate mofetil as an effective corticosteroid-sparing therapy for recalcitrant dermatomyositis. Arch Dermatol. Jan 2006;142(1):65-9. [Medline].

-

Kasteler JS, Callen JP. Low-dose methotrexate administered weekly is an effective corticosteroid-sparing agent for the treatment of the cutaneous manifestations of dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. Jan 1997;36(1):67-71. [Medline].

-

Villalba L, Hicks JE, Adams EM, et al. Treatment of refractory myositis: a randomized crossover study of two new cytotoxic regimens. Arthritis Rheum. Mar 1998;41(3):392-9. [Medline].

-

Dalakas MC, Illa I, Dambrosia JM, et al. A controlled trial of high-dose intravenous immune globulin infusions as treatment for dermatomyositis. N Engl J Med. Dec 30 1993;329(27):1993-2000. [Medline].

-

Woo TY, Callen JP, Voorhees JJ, Bickers DR, Hanno R, Hawkins C. Cutaneous lesions of dermatomyositis are improved by hydroxychloroquine. J Am Acad Dermatol. Apr 1984;10(4):592-600. [Medline].

-

Zieglschmid-Adams ME, Pandya AG, Cohen SB, Sontheimer RD. Treatment of dermatomyositis with methotrexate. J Am Acad Dermatol. May 1995;32(5 Pt 1):754-7. [Medline].

-

Rowin J, Amato AA, Deisher N, Cursio J, Meriggioli MN. Mycophenolate mofetil in dermatomyositis: is it safe?. Neurology. Apr 25 2006;66(8):1245-7. [Medline].

-

Chung L, Genovese MC, Fiorentino DF. A pilot trial of rituximab in the treatment of patients with dermatomyositis. Arch Dermatol. Jun 2007;143(6):763-7. [Medline].

-

Huber A, Gaffal E, Bieber T, Tuting T, Wenzel J. Treatment of recalcitrant dermatomyositis with efalizumab. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86(3):254-5. [Medline].

-

Oliveri MB, Palermo R, Mautalen C, Hubscher O. Regression of calcinosis during diltiazem treatment in juvenile dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. Dec 1996;23(12):2152-5. [Medline].

-

Ambler GR, Chaitow J, Rogers M, McDonald DW, Ouvrier RA. Rapid improvement of calcinosis in juvenile dermatomyositis with alendronate therapy. J Rheumatol. Sep 2005;32(9):1837-9. [Medline].

-

Klein RQ, Bangert CA, Costner M, et al. Comparison of the reliability and validity of outcome instruments for cutaneous dermatomyositis. Br J Dermatol. Sep 2008;159(4):887-94. [Medline].

-

Marie I, Hatron PY, Levesque H, et al. Influence of age on characteristics of polymyositis and dermatomyositis in adults. Medicine (Baltimore). May 1999;78(3):139-47. [Medline].

Further Reading

Keywords

dermatomyositis, idiopathic inflammatory myopathy, dermatomyositis sine myositis, amyopathic dermatomyositis, juvenile dermatomyositis, childhood dermatomyositis, polymyositis, vesiculobullous erosive lesions, exfoliative erythroderma, heliotrope rash, Gottron papules, poikiloderma, calcinosis

Contributor Information and Disclosures

Author

Jeffrey P Callen, MD, Professor of Medicine, Chief, Division of Dermatology, University of Louisville School of Medicine

Jeffrey P Callen, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Physicians, and American College of Rheumatology

Disclosure: Amgen Honoraria Consulting; Abbott Honoraria Consulting; Electrical Optical Sciences Honoraria Consulting; Centocor Honoraria Consulting; Genetech Honoraria Consulting; Celgene Honoraria Consulting

Medical Editor

Kathleen David-Bajar, MD, Former Consultant to the Army Surgeon General, Department of Dermatology, Brooke Army Medical Center

Kathleen David-Bajar, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha and American Academy of Dermatology

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Pharmacy Editor

Richard P Vinson, MD, Assistant Clinical Professor, Department of Dermatology, Texas Tech University School of Medicine; Consulting Staff, Mountain View Dermatology, PA

Richard P Vinson, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Dermatology, Association of Military Dermatologists, Texas Dermatological Society, and Texas Medical Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Managing Editor

Jeffrey Meffert, MD, Assistant Clinical Professor of Dermatology, University of Texas Health Science Center-San Antonio

Jeffrey Meffert, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Dermatology, American Medical Association, Association of Military Dermatologists, and Texas Dermatological Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

CME Editor

Catherine Quirk, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Dermatology, Brown University

Catherine Quirk, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha and American Academy of Dermatology

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Chief Editor

William D James, MD, Paul R Gross Professor of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine; Vice-Chair, Program Director, Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania Health System

William D James, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Dermatology and Society for Investigative Dermatology

Disclosure: elsevier Royalty Other; american college of physicians Honoraria Other