July 11, 2014: On June 18, Aswath Damodaran, a finance professor at NYU’s Stern School of Business, published an article on FiveThirtyEight titled “Uber Isn’t Worth $17 Billion.” This post was a shortened version of a more detailed post he had written for his own blog titled “A Disruptive Cab Ride to Riches: The Uber Payoff.” Using a combination of market data, math, and financial analysis, Professor Damodaran concluded that his best estimate of the value of Uber is $5.9 billion, far short of the value recently determined by the market. This estimate of value was tied to certain “assumptions” with respect to TAM (total available market) as well as Uber’s market share within that TAM. And as you would expect, his answer is critically dependent on these two assumptions.

As the Series A investor and board member at Uber, I was quite intrigued when I heard that there was a FiveThirtyEight article specifically focused on the company. I have always loved the deep, structured analysis that Bill Simmons and Grantland bring to sports, and when Nate Silver also joined ESPN, I was looking forward to the same thoughtful analysis applied to a much broader range of subjects. Deep research and quantitative frameworks are sorely lacking in today’s short attention span news approach. I could hardly wait to dive in and see the approach.

The funny thing about “hard numbers” is that they can give a false sense of security. Young math students are warned about the critical difference between precision and accuracy. Financial models, especially valuation models, are interesting in that they can be particularly precise. A discounted cash flow model can lead to a result with two numbers right of the decimal for price-per-share. But what is the true accuracy of most of these financial models? While it may seem like a tough question to answer, I would argue that most practitioners of valuation analysis would state “not very high.” It is simply not an accurate science (the way physics is), and seemingly innocuous assumptions can have a major impact on the output. As a result, most models are used as a rough guide to see if you are “in the ball park,” or to see if a particular stock is either wildly under-valued or over-valued.

So here is the objective of this post. It is not my aim to specifically convince anyone that Uber is worth any specific valuation. What Professor Damodaran thinks, or what anyone who is not a buyer or seller of stocks thinks, is fairly immaterial. I am also not out to prove him wrong. I am much more interested in the subject of critical reasoning and predictions, and how certain assumptions can lead to gravely different outcomes. As such, my goal is to offer a plausible argument that the core assumptions used in Damodaran’s analysis may be off by a factor of 25 times, perhaps even more. And I hope the analysis is judged on whether the arguments I make are reasonable and feasible.

Damodaran uses two primary assumptions that drive the core of his analysis. The first is TAM, and the second is Uber’s market share within that market. For the market size, he states, “For my base case valuation, I’m going to assume that the primary market Uber is targeting is the global taxi and car-service market.” He then goes on to calculate a global estimate for the historical taxi and limousine market. The number he uses for this TAM estimate is $100 billion. He then guesses at a market share limit for Uber – basically a maximum in terms of market share the company could potentially achieve. For this he settles on 10%. The rest of his model is rather straightforward and typical. In my view, there is a critical error in both of these two core assumptions.

Total Available Market Analysis

Let’s first dive into the TAM assumption. In choosing to use the historical size of the taxi and limousine market, Damodaran is making an implicit assumption that the future will look quite like the past. In other words, the arrival of a product or service like Uber will have zero impact on the overall market size of the car-for-hire transportation market. There are multiple reasons why this is a flawed assumption. When you materially improve an offering, and create new features, functions, experiences, price points, and even enable new use cases, you can materially expand the market in the process. The past can be a poor guide for the future if the future offering is materially different than the past. Consider the following example from 34 years ago that included the exact same type of prediction error:

“In 1980, McKinsey & Company was commissioned by AT&T (whose Bell Labs had invented cellular telephony) to forecast cell phone penetration in the U.S. by 2000. The consultant’s prediction, 900,000 subscribers, was less than 1% of the actual figure, 109 Million. Based on this legendary mistake, AT&T decided there was not much future to these toys. A decade later, to rejoin the cellular market, AT&T had to acquire McCaw Cellular for $12.6 Billion. By 2011, the number of subscribers worldwide had surpassed 5 Billion and cellular communication had become an unprecedented technological revolution.” (article via @trengriffin)

The tweet included here from Aaron Levie highlights the key point we are making – Uber’s potential market is far different from the previous car-for-hire market, precisely because the numerous improvements with respect to the traditional model lead to a greatly enhanced total available market. We will now walk through those key differences, dive deep on the issue of price, and then consider a range of expanded use cases for Uber, including one that changes the game entirely.

The tweet included here from Aaron Levie highlights the key point we are making – Uber’s potential market is far different from the previous car-for-hire market, precisely because the numerous improvements with respect to the traditional model lead to a greatly enhanced total available market. We will now walk through those key differences, dive deep on the issue of price, and then consider a range of expanded use cases for Uber, including one that changes the game entirely.

A Radically Different Experience

- Pick-up times. In cities where Uber has high liquidity, you have average pick-up times of less than five minutes. For most of America, prior to Uber it was impossible to predict how long it would take for a taxi to show up. You also didn’t have visibility into its current location; so having confidence about the taxi’s arrival time was nearly impossible. As Uber becomes more established in a market, pick-up times continue to fall, and the product continues to improve.

- Coverage density. As Uber evolves in a city, the geographic area they serve grows and grows. Uber initially worked well primarily within the San Francisco city limits. It now has high liquidity from South San Jose to Napa. This enlarged coverage area not only increases the number of potential customers, but it also increases the potential use-cases. Uber is already achieving liquidity in geographic regions where consumers rarely order taxis, which is explicitly market expanding.

- Payment. With Uber you never need cash to affect a transaction. The service relies solely on payment enabled through a smartphone application. This makes it much easier to use on the spur of the moment. It also removes a time consuming and unnecessary step from the previous process.

- Civility. The dual-rating system in Uber (customers rate drivers and drivers rate customers) leads to a much more civil rider/driver experience. This is well documented and understood. With taxis, users worry about being taken advantage of, and many drivers spend all day with riders accusing them of such. This can make for an uncomfortable experience on both sides.

- Trust and safety. Most Uber riders believe they are safer in an Uber than in a traditional taxi. This sentiment is easy to understand. Because there is a record of every ride, every rider, and every driver, you end up with a system that is much more accountable than the prior taxi market (it also makes it super easy to recover lost items). The rating system also ensures that poor drivers are removed from the system. Many of the women I know have explicitly stated that they feel dramatically safer in an Uber versus a taxi.

Different Economics

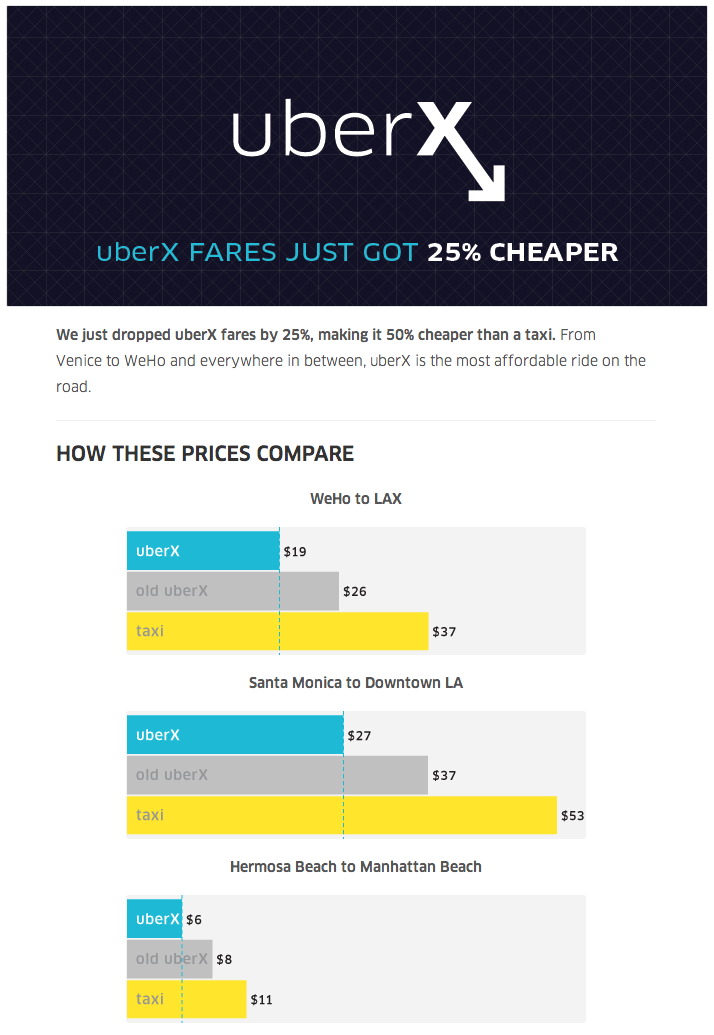

I find it surprising that a finance professor like Damodaran did not consider the impact of price on demand. As Uber becomes more and more liquid, its drivers enjoy higher and higher utilization. Utilization is a measure of the percentage of time drivers are working versus waiting. Think about rides per hour as a similar measurement. As utilization rises, Uber can lower price, and the drivers still make the same amount. Uber does in fact choose to do this, and has done it many times. Just last week, the following email went out to all users in Los Angeles (see graphic below). If you look at the bottom of the graphic, you will see that Uber is now priced dramatically below a taxi. The relationship between price and demand is well understood, and while Damodaran may not have the numbers he would need to calculate Uber’s specific price elasticity, let me assure you that it is high. This only makes sense – lowering the price of car-for-hire transportation will increase the usage.

Most taxi services in the majority of U.S. cities have a fixed supply through some type of medallion system. In NYC today there are 13,605 licensed taxis. In 1937, when the modern system was created, there were 11,787. Additionally, prices only go up, they never go down. How could one possibly know if this is the appropriate supply of taxis and an optimal price point? Doesn’t the high-value of medallions (over $1mm in some markets) implicitly prove that the market is undersupplied and that prices are above true market clearing prices? What if someone could run a more convenient, safer service at a much lower price and with much higher availability? You would end up with dramatically more rides – and that is exactly what is happening.

New Use Cases

- Use in less urban areas. Because of the magical ordering system and the ability to efficiently organize a distributed set of drivers, Uber can operate effectively in markets where it simply didn’t make sense to have a dense supply of taxis. If you live in a suburban community, there is little chance you could walk out your door and hail a cab. And if you call one of the phones, it is a very spotty proposition. Today, Uber already works dramatically well in many suburban areas outside of San Francisco with pick up times in less than 10 minutes. This creates new use cases versus a historical model.

- Rental car alternative. When I used to travel to Los Angeles and Seattle on business I would use a rental car. Today I only Uber. It is materially better. I do not have to wait in lines, and I avoid the needless bus rides on each end of the trip. I don’t have to map routes. I don’t have to find parking. I don’t have to pay for parking. The rental car market is $27B in the U.S. The global market would obviously be much larger. And you are also eating into the parking market here.

- A couple’s night out. The liquidity is so high in the San Jose Peninsula that a couple living in Menlo Park will Uber to a dinner in Palo Alto (perhaps 3 miles away) to avoid the risk of driving after having a glass of wine. This was not a use case that existed for taxis historically. It’s also great for getting from San Francsico back home to the suburbs after a night on the town. This was a historic black car market, but the ease and convenience greatly increases the number of times it is now done, by a multiple.

- Transporting kids. An article in the New York Times titled “Mom’s Van Is Called Uber” suggests that parents are using Uber to send their kids to different events. I don’t think very many people put young kids into taxis (due to trust), but they are quite comfortable doing this in an Uber. It is also common for parents with teenagers to encourage taking Uber when they go out, to reduce the risk that they end up in a car with someone who may have been drinking.

- Transporting older parents. I know many people who are looking after older parents, who have insisted their parents put Uber on their phones to have an alternative to driving at night or in traffic. Convincing them to use Uber is much easier a task than suggesting they call a taxi due to both convenience, ease of use, and social acceptance.

- Supplement for mass transit. If you are someone who primarily uses mass transit, you are likely to consider UberX (low price offering) for exceptions such as when you just miss a train, or when you might be late for a meeting. Lower price points than a taxi and more reliability make this possible. A study from the city of San Francisco argues that more taxis will result in more mass transit use, as it makes it easier not to need a car.

The Game Changer: Uber as a Car-Ownership Alternative

Damodaran likely never considered this possibility: Could Uber reach a point in terms of price and convenience that it becomes a preferable alternative to owning a car? Farhad Manjoo wrote a compelling piece for the New York Times (“With Uber, Less Reason to Own a Car”) making just this argument. And Gregory Ferenstein at VentureBeat dove a little deeper in terms of the math of how this would work. According to Ferenstein, “AAA estimates that the average cost of car ownership per year is about $9,000.” If you take that number and divide it by your average Uber fare you can calculate number of rides you could afford a year, and compare that with what you need. For many, the math is already working. I know numerous people who have already given up their cars, and several people have anecdotally sent photos to Uber of the check they received for selling their car.

Some interesting demographic trends are also underway that favor Uber’s opportunity in this market. First, there is the continuing trend of urbanization in America. But more importantly, America’s youth have fallen out of love with the notion of owning a car. Kids are no longer rushing to obtain their license on the day they turn 16, and according to Edmunds, car ownership among 18-34 year olds has fallen a full 30% in recent years. Here are just a few of many articles published over the past two years on this topic:

- Why Don’t Young Americans Buy Cars? The Atlantic (3/25/12)

- Young Americans ditch the car CNN (9/17/12)

- The End of Car Culture The NYTimes Sunday Review (6/23/13)

- Young Americans Are Abandoning Car Ownership and Driving The Daily Beast (7/5/13)

- The Auto Industry’s Hard Sell to Convince Your Kids They Need a Car Time (1/24/14)

- Millennials Don’t Care About Owning Cars, And Car Makers Can’t Figure Out Why Fast Company (3/26/14)

There are two other points worth considering with respect to Uber as a car ownership alternative. First, the consumer is most likely to replace their “extra” car first. You may see an urban family going from two cars to one. Or perhaps a suburban family will reduce its fleet from four to three or three to two. The fixed costs of this marginal car are very high (DMV registration, insurance, depreciation), yet the usage of that car is much lower. The second point worth nothing is that for certain people the benefits of not driving are so high that they will switch to Uber before the economic case is specifically advantageous, choosing to pay a premium for the convenience. This would include people that consume alcohol after work and do not want to risk driving, people that are frequent users of smartphones when they commute (now considered a bigger risk than DUI), and people that loathe spending time parking their vehicle.

How big is the car-ownership-alternative market?

- According to this NADA report, total dealership sales (including service) is about $730 billion annually. However, that really isn’t what car replacement is all about. Car replacement includes all the costs of owning a car – not just the car purchase, but also insurance, DMV registration, parking, gasoline, repairs, oil changes, etc.

- The number of cars in circulation in the world is just over 1 billion, with 25% of those in the United States. AAA estimates that the average annual cost of owning a car is $9,000. While this number may seem high, if you read the report you will see that the key drivers: the rising costs of gasoline and raw materials and insurance alone averages $1000/year. It is hard to imagine a scenario where these costs fall (most are rising), and many of these costs are now consistent on a global basis. But we will conservatively cut that number by 33% to $6,000.

- One billion global cars multiplied by a $6,000 annual cost of ownership results in a $6 trillion market for annual car ownership costs. How much of that market Uber can take is an interesting question to ponder (which we will), but the fact that 25% of that market is in the U.S. is a huge advantage for the company.

Driving home the point – Uber’s potential market is far different from the previous for-hire market precisely because the numerous improvements over the traditional model lead to a greatly enhanced TAM.

Why only 10%?

Now let’s turn our attention to the 10% maximum market share number that Damodaran chose for his analysis. He argues that regulatory restrictions and competition will limit Uber’s market share. He also makes the point that there are no advantages that cross from city-to-city, a point we will dispute later.

Eighteen years ago, Brian Arthur published a seminal economic paper in the Harvard Business Review titled, “Increasing Returns and the Two Worlds of Business.” If you have not read it, I highly recommend that you do. His key point is that certain technology businesses, rather than being exposed to diminishing marginal returns like historical industrial businesses, are actually subject to a phenomenon called known as “increasing returns.” Gaining market share puts them in a better position to gain more market share. Increasing returns are particularly powerful when a network effect is present. According to Wikipedia, a network effect is present when “… the value of a product or service is dependent on the number of others using it.” In other words, the more people that use the product or service, the more valuable it is to each and every user.

So the right questions are, “is Uber exposed to some form of network effect where the marginal user sees higher utility precisely because of the number of previous customers that have chosen to use it,and would that lead to a market share well beyond the 10% postulated by Damodaran?”

There are three drivers of a network effect in the Uber model:

- Pick-up times. As Uber expands in a market, and as demand and supply both grow, pickup times fall. Residents of San Francisco have seen this play out over many years. Shorter pickup times mean more reliability and more potential use cases. The more people that use Uber, the shorter the pick up times in each region.

- Coverage Density. As Uber grows in a city, the outer geographic range of supplier liquidity increases and increases. Once again, Uber started in San Francisco proper. Today there is coverage from South San Jose all the way up to Napa. The more people that use Uber, the greater the coverage.

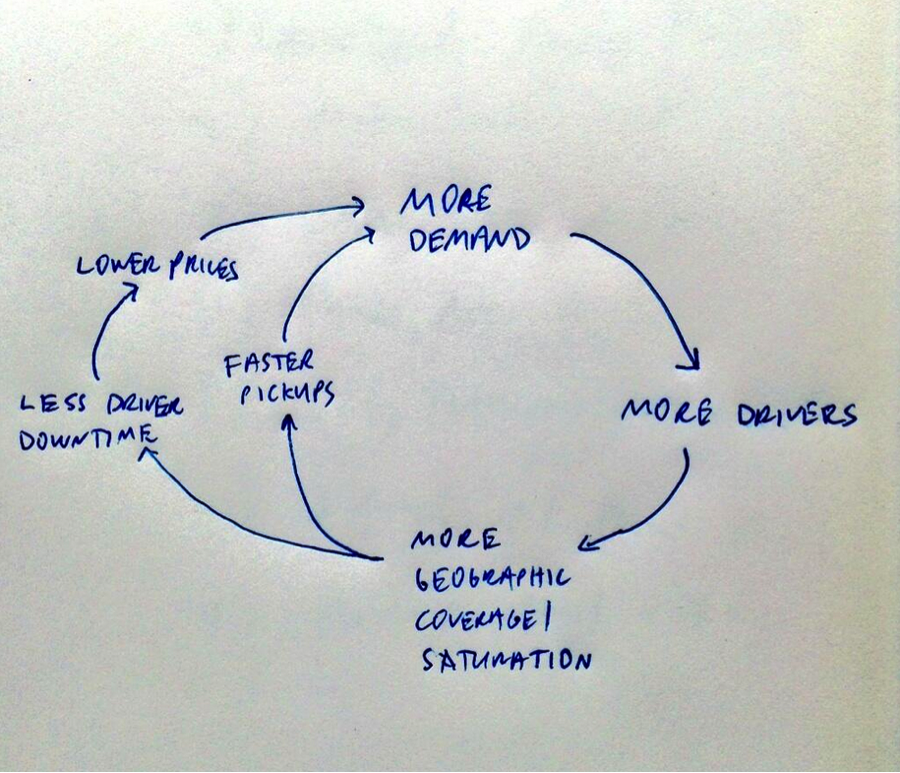

- Utilization. As Uber grows in any given city, utilization increases. Basically, the time that a driver has a paying ride per hour is constantly rising. This is simply a math problem – more demand and more supply make the economical traveling-salesman type problem easier to solve. Uber then uses the increased utilization to lower rates – which results in lower prices which once again leads to more use cases. The more people that use Uber, the lower the overall price will be for the consumer.

David Sacks of Yammer and Paypal, recently tweeted a napkin-sketch captioned, “Uber’s virtuous cycle. Geographic density is the new network effect” that succinctly highlights the points just mentioned.

Uber also enjoys economies of scale that span across city borders. Many people who travel have experienced Uber for the first time in another city. When the company enters a new city they have the stored data for users who have opened the application in that area to see if coverage is available. These “opens” represent eager unfulfilled customers. They also have a list of residents who have already used the application in another city and have a registered credit card on file. This makes launching and marketing in each additional city increasingly easier.

There are other economies of scale that come with being the market leader. When you consider that Uber is partnering with smartphone vendors, credit card companies, car manufacturing companies, leasing companies, and insurance companies, you can imagine that being larger is a distinct advantage. As an example, on May 28th Uber announced a partnership with AT&T to embed Uber on all its Android phones. Then on June 9th, they announced a partnership where American Express users will get 2X loyalty points on all Uber rides. Additionally, Membership Rewards users can use those points to pay for rides directly in the application. It is also easy to imagine a future where Uber drivers receive discounts on things like leases, gasoline and car repair. Scale clearly matters for these types of opportunities.

Undiscovered Clues

There are clues to be found, if you know where to look. In this video recorded in October of 2012 (about 20 months ago), Uber’s CEO, Travis Kalanick, notes that when Uber launched its services in 2010 there were about 600 total black cars in San Francisco. At the time of this video, Travis notes that more than 600 black cars were active on Uber and the company was still growing at 20% month over month (at the time, UberX had just launched, so Uber’s fleet was all black cars). So 20 months ago in San Francisco, Uber was already at 100% of Damodaran’s historic market, and growth was still tilting up and to the right. The only way this is possible is if the market is expanding at rapid pace, beyond the historical limit.

More recently in a WSJ interview dated June 6, 2014, Travis notes “When we got this company started (in 2009) we were pitching the seed round and we pulled a bunch of research from this report that showed that San Francisco total spend on taxi and limo was like 120 million bucks. But we’re a very healthy multiple bigger than that right now, just Uber in SF. So it’s not about the market that exists, it’s about the market we’re creating.” He then goes on to note that the San Francisco market for car ownership is closer to $22 billion. So today, less than two years after the video, he is highlighting that Uber’s San Francisco revenues are a “healthy multiple” bigger than the historic market for both limousines and taxis. And Uber is still growing quite nicely in that market. Plus there are other competitors in the market. So Damodaran’s math simply does not hold up. This cannot be yesterday’s market.

There is another quite simplistic methodology that might have helped Professor Damodaran avoid his unnecessary error. He could have simply asked his friends that were moderate to heavy Uber users the following question: “How does your current annualized Uber expenditures compare to your spend on taxis plus limousines two years ago?” For most of the people I know, the answer to this question is somewhere north of three times as large. That data point alone implies that this is an entirely new market.

Our Proposed Estimates (25x)

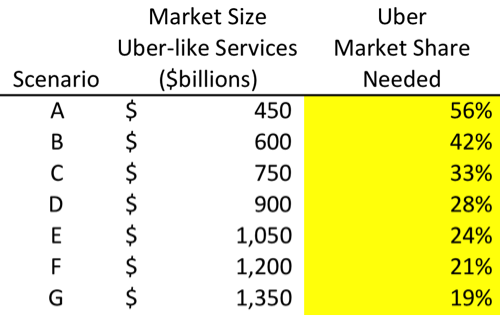

So now let’s consider scenarios whereby Uber’s potential market could be 25 times higher than Damadoran’s original estimate. His original estimate was based on Uber topping out at 10% of a $100 billion market. We would argue, for the reasons included herein, that the features and functions of Uber’s new car-for-hire service significantly expands the core market. Based on San Francisco alone, it appears that that market is already potentially 3X the original. For two reasons, I would consider this 3X market multiplier the low end of the range. First, Uber is still growing aggressively in San Francisco, so this new market is far from saturated. Also, when you consider that these services are succeeding in areas where taxis were previously not prevalent, this would imply a higher multiplier as well. In our model below, we assume that the expanded car-for-hire market is 3-6X bigger than the historic market.

Now we consider Uber-like services as a car ownership alternative. This trend is just beginning, but because of the points highlighted herein, we believe this to be a real opportunity. For our model, we assume that Uber-like services will encroach on a mere 2.5%-12.5% of this market. This represents a potential opportunity of $150-$750 billion depending on how aggressively one believes these services can succeed as a car alternative.

Combining these two opportunities, you end up with a potential range of new TAM estimates from $450 billion all the way up to $1.3 trillion. Now we calculate the market share Uber would need against these new TAM estimates to arrive at an opportunity that is 25X that of Damadoran’s $10B. The table below shows those estimates. In the most bearish case (Scenario A) where the expanded market opportunity is capped at 3X and these new services only marginally impact car ownership, Uber would need a market share of 56%. Arguably it already has that share today, and this number is not unreasonable in a world of network effects (a point that Damadoran cedes in a more recent post). In the case I think is more likely (Scenario G), the expanded market multiplier is 6X and you see a 10% impact on global car ownership, Uber’s market share need only be in the 20% range. Once again, the fact that the U.S. represents 25% of the car-ownership market adds more likelihood to Uber’s ability to capture that opportunity.

As discussed up front, the key objective of this exercise is to present a reasonable and plausible argument that Uber’s market opportunity might be 25X higher. Interestingly, this case is made without any consideration for whether Uber can impact the logistics market or expands into any incremental services whatsoever. We have simply taken a structured look at how traditional human car transportation can change as a result of today’s technology.

There are many biases that can come into play when making estimates. For example, as an investor and board member at Uber one might conclude that I am biased to see things in a more positive light. That would only make sense. In the conclusion to his original post, Damadoran made a similar argument, “it is worth remembering that even smart investors can collectively make big mistakes, especially if they lose perspective.” Somewhere in the editing process between Damadoran’s original post on his web site, and the version that ended up on FiveThrityEight, this little nugget was left out:

“As I attempt to attach a value to Uber, I have to confess that I just downloaded the app and have not used it yet. I spend most of my of life either in the suburbs, where I can go for days without seeing a taxi, or in New York City, where I find that the subways are a vastly more time-efficient, cheaper and often safer mode of transportation than taxis.”

Great post Bill.

In the long run I think Uber’s toughest competition will be Google rather than any direct competitors. As self driving cars become ubiqutious Google might want to distribute transportation services via its own network.

I am more skeptical. I think that self-driving cars makes for interesting PR, but in many ways it mirrors Bill Gates long obsession with voice input. People will only tolerate marginal error. Machines replacing human judgment fall short. Way short. Imagine if self-driving cars could achieve 99% good decisions. This would make them a pathetic alternative for human drivers that would need to be removed from the street. That is a very high bar.

Why? Google has investment in Uber, Google can provide API for its email, calendar, Now services. Google can sell self-driving car, or license technology for it to Uber.

Which is why Google Ventures is one of the largest stakeholders in Uber

Given Google’s $258 investment in Uber, Google will likely be a partner more than a competitor. This can already be seen with the Uber integration into Google Maps. Also, what’s the most likely initial use case of self-driving cars? It’s unlikely personal ownership and more likely a taxi service that can reduce its costs of driver salaries.

Excellent thrashing! Could Uber be the first to $1 trillion in revenues?

There are many times when I will drive to work but have a meeting somewhere else in the middle of the day. Rather than leave my desk a few minutes early to walk to the garage to get my car out, I’d rather leave the car in the garage and just run down to street level at the last minute and jump in an Uber. Besides that benefit, I can rest easy knowing that I don’t have to concern myself with the parking situation on the other end or the parking fee to get my car out after that meeting. Further, unless you have a monthly pass, most parking garages do not have “in and out privileges” which means I would have had to pay the non-early bird rate to get back into my garage after that meeting. That could amount to another $20-$30 for the rest of the afternoon depending on your garage and the city you live in.

Great post Bill. I’d be very curious to hear your perspective on competition and quality of supply. At some point, it feels like Uber, Lyft, Sidecar and others will have to compete for the same crop of drivers (people with clean records, with safe cars, who can get you from point A to point B safely). That has to be a finite number of drivers per metropolitan area. Do you have any thoughts on if/how that affects market size?

Read my points on network effects. In 1997 Reel.com and CDnow assumed that Amazon.com would only stay in books.

Great points Bill.

I would like to point out that in India Taxi drivers (or Taxi ecosystem) is treated with 100% skepticism. Once UberX (because Indians are cost conscious:) ) becomes a well known brand then the potential market is impossible to imagine.

Am sure same applies to 1000s of cities across the world.

Very interesting analysis!

Thanks for diving deep here.

Thanks for the great post, Bill.

I want to add 2 more network effects to your list:

1. The rating database of drivers and passengers becomes more and more valueable both for drivers and for passengers.

2. The IT integration: Apps for different plattforms, Integration in other systems/apps/services, like Google Now, Maps, Travel planning apps, public transport Apps, Siri

thanks for this article Mr. Gurley. question: how do you see competition compressing that 20% margin over time?

@Ramy, I do agree with you that the main assumption is certainly the ability to keep 20% margin for perpetuity.

I guess that the writer is mislead about one topic: taxis are unaffordable in rich countries; in poor countries people use every single day the taxi: to buy food, to go to work, to the cinema etc.

Will the rich countries be sufficient to sustain the growth and keep the high margin?

@bgurley – Your points on TAM in developed markets do make a plausible argument. having said this, am keen to understand your thoughts on Uber’s play in developing markets where my thoughts against each of those levers is captured below:

– use in less urban areas – am assuming tier 3/4 cities are not on uber’s radar as of now

– rental car alternative – both private and government players are already doing this with considerable success and reliability

- Kids going to school – there is a strong culture of using the school bus or parents dropping the kids off (sometimes they car pool as well). And given that there are restrictions around how far your home should be (3-4km) by top schools, time taken should not be too much of a hassle.

– sending aged parents – smart phone penetration is low among aged parents, and in India young ppl > old people.

– Couples going for a dinner – yes a potential market with increased focus on drunken driving in metros. Again the market is being addressed by local players like Meru, Ola at a cheaper price point. (unless UberX lowers it further)

– supplement for mass transit – Not sure if Uber can be the solution for india’s need for public transport. You should look at the share auto concept – a hugely popular and economical one as well.

how they were before – http://bit.ly/1y2t221

and how India’s premium auto brand capitalised on this market – http://bit.ly/1y2sTM1

looking forward to your thoughts t on what do you think are Uber’s opportunities in emerging markets like India and China. And thanks for pointing me to Brian Arthur’s paper, indeed a wonderful read.

Aren’t you assuming that shared, group and public transportation will remain the same? For example, what about the effect of a magical ordering system and the ability to efficiently organize a distributed set of drivers and passengers on these modes of transport? (We could even go further and talk about changes in the need for transportation, like telecommuting, virtual workplaces and online learning.)

And yet, shared, group and public transportation might be future opportunities for Uber, if those modes of transportation can be recreated by Uber.

Very well done post which will be helpful for many to understand the thought process behind arriving at a workable TAM and plausible revenue and valuation range.

I do find that academics and even some senior management teams don’t seem to have their head wrapped around this kind of thought process. Publishing a flawed article does little damage but sometimes a management team ends up ruining a perfectly good company because they embark on a business model aimed at a TAM that wasn’t correct in the first place.

In any case fine work from a fine analyst. Thanks for taking the time to share it!

What happens when you consider more than just San Francisco? The original estimate was based on global market, and the world is a big place. Specifically, its a big place that’s usually very unlike San Francisco.

We obviously have way more data than just SF, and the wherewithal to judge that question.

Great article thanks. One area that I would like your insight on is the vested interest of the current taxi and limousine business. Where I live the taxis are limited and licensed (ie medallion). Government, bureaucracy and current license holders have a cornered market. They also typically have and edge with local media. Sometimes this vested interest embraces the safety as a barrier to alternate approaches to their approach. Your thoughts and comments on this element of the competition and effect on market size and growth.

The other obvious error is thinking that Uber is a transportation company. Seems to me it’s a fractional asset management company. Much bigger opportunity.

#3 should read “…you don’t need cash to *effect* a transaction…”

Thanks for sharing your thoughts. It would be great if you could elaborate more on your thoughts about the price elasticity of UberX (or maybe they are still developing since the price cuts are an experiment). Airlines and hotels often use price discounts to stimulate demand. Some airlines can stimulate traffic in major leisure markets, but with the aim of making money on ancillary revenues. But there are only a few major markets where that works. Hotels have found that lowering prices does not increase demand enough to offset the decline in prices (and they don’t receive a boost in ancillary revenues). Many hotels see occupancy rates still decline anyway.

The other problem is that when you stimulate demand with low prices, the variable costs increase. In the case of airlines, it’s mainly fuel. In the case of hotels, it’s labor (more people needed for cleaning, laundry, etc). This pressures margins since your costs are higher, but your price is now lower. With more trips, the UberX driver will have higher variable costs, especially fuel. I’m not sure the $1,000 weekly guarantee will be enough to offset the lower margins since it seems to be a gross revenue guarantee. If the margins are too low, it could be that drivers decide not to drive because it isn’t worth it on a net basis. This speaks to the point that Sunil Rajaraman made. Is there a natural limit to the amount of drivers (perhaps exacerbated by the price discounts)? Will it be even tougher to recruit drivers now given the recovery in the US labor market?

TAM is definitely not the way to evaluate Uber or any on demand service. Bottom line, the Ubers of the world are building new markets of services that people don’t even know they need. Its like looking at Amazon through a TAM lens in 1998.

Uber is a gamechanger to the transportation industry, and it’s impossible to look backward when gauging the size and impact of such a tectonic shift. I write this as I am visit Dallas for several days – Uber’ing everywhere I go – saving money, time, and convenience over the rental car I’ve used on previous trips.

Well done Bill. Uber has already solidly crossed the go big or go home line. I was/maybe still am a disbeliever in the sustainability of core service, even as a passionate user. Still the leap of faith that take the company from great to unbelievable is the argument that company can be behaviorally transformative to disrupt many industries. I love the vision and am basically a believer. Still, I have a voice in my head reminding me changing one behavior is hard, changing multiple multiple behaviors well… the voice says get a snack cause this will be worth watching.

Love this… Anyone attempting to value Uber without experiencing Uber is futile and irresponsible.

To your point on how incorrect assumptions produce dramatically incorrect valuations, it’s highlighted here on this recent NYT article on golf course real estate crash — http://nyti.ms/1nlMFyH

“The biggest frenzy was in the late 1990s, Mr. Affeldt said, after an ‘erroneous report’ said that the supply of golf courses would not be sufficient to accommodate retiring baby boomers. Between 1994 and 1999, the market added on average a net 343 courses a year….

What the projections did not account for, however, was changing behavior among retirees….While plenty of baby boomers still love to golf, he said, many are working longer, traveling more and taking up other leisure activities. Meanwhile, the younger set has not given the industry much of a bump. “The family dynamic has changed,” Mr. Hirsh said. “Dad’s not leaving for the golf course at 8 o’clock Saturday morning and coming home just in time for dinner.”

With Uber, the service has driven the behavior change.

My question is more on growth rate, not TAM. After all, Uber is a service company that needs human beings (for now, unless self-driving cars become ubiquitous) to scale. Typically, those types of businesses have not scaled as fast. How fast can Uber scale?

Bill

Anecdotal evidence is on your side. My house in SF is located next to Candlestick Park, and for a short trip to the airport, I could never get a taxi to show up on time, and half the time not at all. With Uber, the car arrives in minutes.

To expand, this morning it was announced that Lyft had a temporary injunction imposed here in NY when they were going to launch in Brooklyn and Queens.

http://www.businessinsider.com/lyft-delays-nyc-launch-2014-7

The market is definitely expanding well beyond the previous calc’s.

Marc

Great post. Re network effects and virtuous cycles, do you have any heuristics for the early detection of a leadership position which has become durable and unlikely to be reversed? Thanks

I would be interested in seeing the tax benefits from Uber paying taxes vs traditional taxis paying taxes. Taxis are predominately cash based. While taxi drivers will claim its to save on credit card fees, I am confident that they hide a decent portion from IRS. Because Uber is all credit card based, it is unlikely that Uber is hiding any from IRS.

You are essentially saying demand for local transportation is elastic to price and to a certain extent to quality. Maybe Damodaran missed it but this is not new.

The virtuous economics described actually apply in the same way to taxis. There are cities in the world where taxis are cheap and safe and used a lot (Bucharest, Romania is one example I know of).

The issue with the taxi market in the US is that it is not a free market but artificially under supplied due to local monopolies / oligopolies – as the post notes. The simple existence of dirty / smelly cabs with rude drivers is enough to tell one there’s competition failure in this market.

Uber circumvents the competition limiting regulations and that seems to be more important an “innovation” than the other easy to copy bells and whistles – track route, better prediction, easy payment etc.

Uber needs political support to edge out these monopolies that ensured bad service since forever.

Bill, I’d love to get your view of how Uber plays into the multi-modal end -to-end transportation journey. What I am hearing from many transportation providers is that they are expanding from single to multi-modal transportation services ; trains + buses + ride sharing services., etc… and the challenge is integrating all of the “moving parts” into a single service. And then building a set of personalized services on top of the physical services for the traveler. This increases stickiness and disintermediation of a single mode/segment provider .

Bill – Great analysis as usual. Lot of the great explanation is this post hones in two concepts that surprisingly were missed out Mr Damodaran.

(a) Manufacturing new demand (or) Converting non-consumers: Taxi market dying is a consequence and not the only market Uber is operating in.

(b) Blue Ocean Strategy – Offering differentiated value: Not fighting on uniquely just cost, but comfort, trust, reliability,high availability, transparency, etc..etc.

I find Uber brilliants hits both of these and excitingly enough, not to mention all customers become repeat customers.

I feel this article left out a couple of interesting points:

(a) The article missed out on multi passenger rides: I notice in my frequent travels that India (specifically south India) has a concept of “shared taxis” wherein private vehicles that seat upto 10 people periodically run(operated by private citizens – much similar to Uber) on the same route as public vehicles with much better transit times, predictability and comfort at lower prices. So to the great list above, add replacement of MUNI, BART, train lines all around, Greyhound, Amtrak, school buses etc. Over the last 6-7 years the “shared taxi” model has pretty much changed the landscape of public transport in South India. Happy to talk to someone in Uber if they need more breakdown. If you travel by land, Uber will take over that market and adjacencies around it.

(b) I interview every Uber driver I encounter. Around 20- 30% of them are buying new cars (some of them hybrid) to use for the business(Uber) already. Though car ownership models might change for the end consumer, Uber is primed to replace Avis, Hertz, Dollar and every other car rental agency. Uber will herald the new “services revolution”. So market size will include the “entire” rental car market spend.

(c) Health care services: There is also a huge market to transport the disabled (currently privatized to specific operators or care givers) and traditionally paid by the insurance companies (payers). With trust , reliability and availability increase, these services will add to the market size as well.

Add to all this the fact that we are not talking outside of human transportation yet and not owing any of the transportation assets. My numbers come at a much higher multiple.

Cheers

VJ

Great analysis, and I agree that Uber is undervalued at $17B. However, I believe you are actually still undervaluing Uber and discounting the potential of self-driving vehicles. 90% of accidents are due to human failure so I’m not sure why an autonomous vehicle needs to be 100% fail safe. Planes and trains aren’t either, even those which are today effectively “self-driving”. Given that rush hour in major cities is often <10 mph and max speed is typically not much over 25, which are low risk speeds, there should be opportunities for autonomous urban vehicles given new physical infrastructure & policy. It's not clear to me that Uber has the right strategy to be first mover in this space (though I think Upshift has) given that full autonomous in an urban area is much harder than other use cases but they ought to have a significant opportunity to capitalize on it eventually given their partnership with Google. SDCs need not be perfect for all use cases to be worthwhile, they just need to be good enough for parallel and niche markets like carshare, rideshare, etc. I'd imagine that the average user may find voice recognition software "not good enough yet" but I'd suspect there is a large contingent who have few alternatives (eg, those with disabilities) who find it much better than their alternatives. Assuming Google's moonshot ever turns out correct, there are many many more opportunities for Uber than anyone is currently discussing. We are still in the nascent days of a fundamental disruption in the multi-trillion dollar industry you named and Uber is doing a compelling job of scratching the surface as you point out. Thanks for the post.

Fantastic insights and I love how each point is well substantiated with evidence and not just bias (though you have chosen to deflect that potential accusation towards the end too!) which could’ve easily crept it.

3 things around the same subject that stand out for me which could further spiral Uber’s growth and numbers –

> Uber isn’t on Windows Phone yet. While it may only be 4% of the global smartphone market, 11% & 7% of that total is currently in US & India – two markets very much in Uber’s radar, the former more obvious than the latter. Gartner suggests that by 2018, WP could account for 10% of the world’s base.

> Markets like India, Philippines and Indonesia are seeing smartphone adoption at a crazy pace. While the dominant reasons for adoption are probably societal, social and messaging, as users mature, they are going to resort to using their available app eco-system to improve their quality of life. That’s where I see the 20% feature-phone users who don’t buy smartphones, adding in droves to Uber’s user base in the Asia-Pac region.

> UAE – The country with the world’s highest penetration of smartphones and with 9.9 million tourists each year is yet to see significant adoption of Uber. While UberBlack is the only available option currently, I see huge potential for UberX in Dubai. The same may or may not apply to other countries in the GCC where Uber is present.

What a rebuttal, thanks for that Bill.

One thing left me curious – you don’t mention the market of courier services which Uber can (and has started to) eat into, how big do you think that is? And what are some other uses you can see that leverage the ‘digital mesh’ created with a phone in everyone’s pocket?

Completely agree with article. .very well written and presented facts objectively without being emotional. I started using Uber about 8 months ago and I travel A LOT. For all the reasons mentioned above I haven’t even used any other taxi other than Uber. In fact I was disappointed that indian uber did not accept my US based account. That is another thing uber will improve on..global consistency and freedom from thinking how to hail a taxi in a foreign country. I am really envisioning a world where through Uber we can order for freight services on the go..tankers, ships..u name it. I am a believer

I’m not sure if this represents a limiting factor, but I remain fascinated by the counter-intuitive behaviour displayed by taxi drivers in many countries – namely that they work as long as it takes to reach a set level of daily income and then go home rather than maximise revenue beyond that level reagrdless of customer demand. Perhaps, Uber drivers behave differently.

I’m not sure if this represents a limiting factor, but I remain fascinated by the counter-intuitive behaviour displayed by taxi drivers in many countries. Namely, that they work as long as it takes to reach a set level of daily income and then go home regardless of the existence of further customer demand. Perhaps, Uber drivers behave differently.

There’s also another way to slice the market sizing. Look at the cutoff point of miles driven where switching to uber makes sense.

The average US trip is about 10 miles – uber would charge about $24 for this assuming 30mph average. Adjusting for gas expenses (at 30mpg or so) – the cost per mile compared to car is about $2.15 per mile. Assuming an average car depreciation of $2k per year + insurance + repair, a car costs about $4-5k per year (ish.). So you’d have to be driving less than 3k’ish miles per year in order for it to be worth ubering full time.

About 25% of US cars drive fewer miles per year than this. So there’s a potential maximum market of about 50 billion miles (+/-10billion) driven that’s available for switchover to Uber (assuming about 1k average for the switch-overs and some reduction for rural and misc. non-serviceable areas). At a $2.4 per mile revenue- that’s a $120 billion maximum “low-mileage” car replacement market.

One should also consider other, related, advancements such as ever-more reliable grocery delivery and the overall rise of eCommerce. These lead to fewer personal car trips to stores that involve bags of goods. Ordering from Amazon Fresh means one less reason to own a car and likely a few more percentage points in your car-alternative model. I sense a BD deal…

If Uber offered a Zipcar competitor (UberGO?) that placed a flexible fleet of reservable cars within a 5m walk, it is reasonable to believe that most urban households could give up their personal vehicle on a purely economic basis.

Now what to do with all those empty garages?

The use cases for Uber keep on expanding, and the service is indeed creating a new market that never before existed. Case in point, getting stuck half way across the city and instead of walking home I just put out a beacon for UberX and had a driver to me in 5 minutes. Short rides, long rides, it doesn’t matter; my behavior has changed as a result of this service. I no longer feel the need to own a car, and much of that money saved will be redistributed to Uber.

Excellent article, thank you for sharing your thoughts. I am an equity analyst in public markets (pertinent to the post). The article clearly shows the difference in the thought process of Mr. Gurley and Mr. Damodaran that is driven by incentives. From what I understand in VC, the bigger risk is missing the next big thing as returns are driven by a few 10x or more ideas while the failure rate of investments are very high so the thought process needs to be thinking about what is the potential market. The incentive of someone who already owns the company is to talk up the market size to get a larger valuation on exit.

For someone investing at public markets (not speculating or institutional investors worrying about a benchmark), the biggest risk is permanent loss of capital. The investor is to err on the side of conservatism. Thinking about potential markets and new uses is great but Valuation is a crap shoot so you do not want to overpay on the premise of future markets and new uses for a product as it eliminates an investors margin of safety, which usually leads to permanent loss of capital.

For every Uber that may/will deliver on its potential, there are 9 other companies that make the same promises and do not deliver. In the VC world the risk is not identifying the Uber of the 10 while in public markets the risk is investing in the other 9.

Very well thought out and written post Bill — though not surprised coming from a Gator..:-)

I do find it funny how some so called experts — whether it be academia or Execs tout and argue their points with out actually researching and trying out the product/service and experiencing it personally..

I do think think Uber is creating a truly remarkable marketplace for transportation services. I do believe it the network affect will get bigger and more mainstream.

The one risk I fear may derail some of the momentum is regulatory. I do see local governments imposing undue burden on Uber due to pressure from taxi companies. Will the product experience and consumer activism trump that regulatory pressure? Who knows but mitigating that risk by constantly maintaining product experience both for drivers and consumers will determine if Uber can attain that $1 T in revenues?

As an entrepreneur who’s been trying to size the non-trivial TAM of the industry I’m working in, I loved being taken through this cast study.

One potential oversight I see here is the potential size of Uber Rush on the courier/logistics business. If Uber can move people from A -> B, it can certainly move objects – though unsure how the economics work out.

Given Bill’s inisjght into the business I wonder whether this post implies Uber’s long term focus on moving people and not things.