2011 Egyptian revolution

| Egyptian Revolution of 2011 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Arab Spring | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Demonstrators in Cairo's Tahrir Square on 8 February 2011 | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Number | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

| This article is part of the series: Politics and government of Egypt |

The Egyptian Revolution of 2011 (Arabic: ثورة 25 يناير thawret 25 yanāyir, Revolution of 25 of January) took place following a popular uprising that began on 25 January 2011. It was a diverse movement of demonstrations, marches, plaza occupations, riots, non-violent civil resistance, acts of civil disobedience and labor strikes. Millions of protesters from a variety of socio-economic and religious backgrounds demanded the overthrow of the regime of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak. There were also important Islamic, anti-capitalist, nationalist, and feminist currents of the revolution. Violent clashes between security forces and protesters resulted in at least 846 people killed and 6,000 injured.[20][21] Protesters also burned upwards of 90 police stations, though international media and politicians attempted to minimize that aspect of the revolt.[22] Protests took place in Cairo, Alexandria, and in other cities in Egypt, following the Tunisian revolution that resulted in the overthrow of the long-time Tunisian president.

Grievances of Egyptian protesters were focused on legal and political issues[23] including police brutality, state of emergency laws,[1] lack of free elections and freedom of speech, corruption,[2] and economic issues including high unemployment, food price inflation[3] and low wages.[1][3] The primary demands from protesters were the end of the Hosni Mubarak regime, the end of emergency law, freedom, justice, a responsive non-military government and a say in the management of Egypt's resources.[24] Strikes by labour unions added to the pressure on government officials.[25]

During the uprising the capital city of Cairo was described as "a war zone"[26] and the port city of Suez saw frequent violent clashes. The protesters defied the government imposed curfew and the police and military did not enforce it. The presence of Egypt's Central Security Forces police, loyal to Mubarak, was gradually replaced by large restrained military troops. In the absence of police, there was looting by gangs that opposition sources said were instigated by plainclothes police officers. In response, watch groups were organised by civilians to protect neighbourhoods.[27][28][29][30][31]

International reactions have varied with most Western states saying peaceful protests should continue but also expressing concern for the stability of the country and the region. The Egyptian revolution, along with Tunisian events, has influenced demonstrations in other Arab countries including Yemen, Bahrain, Jordan, Syria and Libya.

Mubarak dissolved his government and appointed former head of the Egyptian General Intelligence Directorate Omar Suleiman as Vice-President in an attempt to quell dissent. Mubarak asked aviation minister and former chief of Egypt's Air Force, Ahmed Shafik, to form a new government. Mohamed ElBaradei became a major figure of the opposition, with all major opposition groups supporting his role as a negotiator for some form of transitional unity government.[32] In response to mounting pressure, Mubarak announced he had not intended to seek re-election in September.[33]

On 11 February 2011, Vice President Omar Suleiman announced that Mubarak would be stepping down as president and turning power over to the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) and Mubarak resigned from office.[34] The military junta, headed by effective head of state Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, announced on 13 February that the constitution would be suspended, both houses of parliament dissolved, and that the military would rule for six months until elections could be held. The prior cabinet, including Prime Minister Ahmed Shafik, would continue to serve as a caretaker government until a new one is formed.[35] Shafik resigned on 3 March, a day before major protests to get him to step down were planned; he was replaced by Essam Sharaf, the former transport minister.[36] On 24 May, Mubarak was ordered to stand trial on charges of premeditated murder of peaceful protestors and, if convicted, could face the death penalty.[12]

On 2 June 2012, Mubarak was found guilty of complicity in the murders of the protestors and sentenced to life imprisonment, but this sentence was later overturned on appeal.[37] Numerous protesters upset that others tried with Mubarak, including his two sons, had been acquitted, took to the streets.[38] On 19 June, protesters, many belonging to the Muslim Brotherhood, protested in Cairo's Tahrir Square, angry that the SCAF had taken some of the powers that had formerly belonged to the President. Protesters also accused the SCAF of launching a coup. On 24 June, the State Election Commission announced that Islamist Mohammed Morsi had won the presidential election. On 30 June, Morsi was inaugurated as the 5th President of Egypt.

On 3 July 2013 Mohammed Morsi was deposed in a military coup.[39] Egypt will have an interim government until a new election. The interim government was supported by the army and opposed by the Muslim Brotherhood.

Contents[hide] |

Naming[edit]

In Egypt and the wider Arab world, the protests and subsequent changes in the government have generally been referred to as the 25 January Revolution (ثورة 25 يناير Thawrat 25 Yanāyir), Freedom Revolution (ثورة حرية Thawrat Horeya),[40] or Rage Revolution (ثورة الغضب Thawrat al-Ġaḍab), and less frequently,[41] the Revolution of the Youth (ثورة الشباب Thawrat al-Shabāb), Lotus Revolution[42] (ثورة اللوتس), or White Revolution (الثورة البيضاء al-Thawrah al-bayḍāʾ).[43]

Background[edit]

Hosni Mubarak became head of Egypt's semi-presidential republic government following the 1981 assassination of President Anwar El Sadat, and continued to serve until 2011. Mubarak's 30-year reign made him the longest-serving President in Egypt's history,[44] with his National Democratic Party (NDS) government maintaining one-party rule under a continuous state of emergency.[45] Mubarak's government earned the support of the West and a continuation of annual aid from the United States by maintaining policies of suppression towards Islamic militants and peace with Israel.[45] Hosni Mubarak was often compared to an Egyptian pharaoh by the media and by some of his critics due to his authoritarian rule.[46]

Inheritance of power[edit]

Gamal Mubarak, the younger of Mubarak's two sons, began to be groomed to succeed his father as the next president of Egypt around the year 2000.[47] Gamal started receiving considerable attention in the Egyptian media, as there were no other apparent heirs to the presidency.[48] Bashar al-Assad's rise to power in Syria in June 2000, just hours after Hafez al-Assad's death, sparked a heated debate in the Egyptian press regarding the prospects for a similar scenario occurring in Cairo.[49]

In the years after Mubarak's 2005 reelection several political groups (most in Egypt are unofficial), on both the left and the right, announced their sharp opposition to the inheritance of power. They demanded political change and asked for a fair election with more than one candidate. In 2006, with opposition rising, The Daily News Egypt reported on an online campaign initiative, called the National Initiative against Power Inheritance, which demanded Gamal reduce his power. The campaign stated, "President Mubarak and his son constantly denied even the possibility of [succession]. However, in reality they did the opposite, including amending the constitution to make sure that Gamal will be the only unchallenged candidate."[50]

Over the course of the decade perception grew that Gamal would succeed his father. He wielded increasing power as NDP deputy secretary general, in addition to a post he held heading the party's policy committee. Analysts went so far as describing Mubarak's last decade in power as “the age of Gamal Mubarak.” With Mubarak’s health declining and the leader refusing to appoint a vice-president, Gamal was considered by some to be Egypt's de facto president.[51]

Both Gamal and Hosni Mubarak continued to deny that an inheritance would take place. There was talk, however, of Gamal being elected; with Hosni Mubarak's presidential term set to expire in 2010 there was speculation Gamal would run as the NDP party's candidate in 2011.[52]

After the January–February 2011 protest, Gamal Mubarak stated that he would not be running for the presidency in the 2011 elections.[53]

Emergency law[edit]

An emergency law (Law No. 162 of 1958) was enacted after the 1967 Six-Day War. It was suspended for 18 months in the early 1980s[54] and has otherwise continuously been in effect since President Sadat's 1981 assassination.[55] Under the law, police powers are extended, constitutional rights suspended, censorship is legalised,[56] and the government may imprison individuals indefinitely and without reason. The law sharply limits any non-governmental political activity, including street demonstrations, non-approved political organizations, and unregistered financial donations.[54] The Mubarak government has cited the threat of terrorism in order to extend the emergency law,[55] claiming that opposition groups like the Muslim Brotherhood could come into power in Egypt if the current government did not forgo parliamentary elections and suppress the group through actions allowed under emergency law.[57] This has led to the imprisonment of activists without trials,[58] illegal undocumented hidden detention facilities,[59] and rejecting university, mosque, and newspaper staff members based on their political inclination.[60] A parliamentary election in December 2010 was preceded by a media crackdown, arrests, candidate bans (particularly of the Muslim Brotherhood), and allegations of fraud involving the near-unanimous victory by the ruling party in parliament.[54] Human rights organizations estimate that in 2010 between 5,000 and 10,000 people were in long-term detention without charge or trial.[61][62]

Police brutality[edit]

According to a report from the U.S. Embassy in Egypt, police brutality has been common and widespread in Egypt.[63] In the five years prior to the revolution, the Mubarak regime denied the existence of torture or abuse carried out by the police. However, many claims by domestic and international groups provided evidence through cellphone videos or first-hand accounts of hundreds of cases of police abuse.[64]

According to the 2009 Human Rights Report by the U.S. State Department, "Domestic and international human rights groups reported that the Ministry of Interior (MOI) State Security Investigative Service (SSIS), police, and other government entities continued to employ torture to extract information or force confessions. The Egyptian Organization for Human Rights documented 30 cases of torture during the year 2009. In numerous trials defendants alleged that police tortured them during questioning. During the year activists and observers circulated some amateur cellphone videos documenting the alleged abuse of citizens by security officials. For example, on 8 February, a blogger posted a video of two police officers, identified by their first names and last initials, sodomizing a bound naked man named Ahmed Abdel Fattah Ali with a bottle. On 12 August, the same blogger posted two videos of alleged police torture of a man in a Port Said police station by the head of investigations, Mohammed Abu Ghazala. There was no indication that the government investigated either case."[65]

The deployment of plainclothes forces paid by Mubarak's ruling party, Baltageya,[66] (Arabic: بلطجية), has been a hallmark of the Mubarak government.[66] The Egyptian Organisation for Human Rights has documented 567 cases of torture, including 167 deaths, by police that occurred between 1993 and 2007.[67] Excessive force was often used by law enforcement agencies. The police forces constantly quashed democratic uprisings with brutal force and corrupt tactics.[68] On 6 June 2010 Khaled Mohamed Saeed died under disputed circumstances in the Sidi Gaber area of Alexandria. Multiple witnesses testified that Saeed was beaten to death by the police.[69][70] A Facebook page called "We are all Khaled Said" helped bring nationwide attention to the case.[71] Mohamed ElBaradei, former head of the International Atomic Energy Agency, led a rally in 2010 in Alexandria against alleged abuses by the police and visited Saeed's family to offer condolences.[72]

During the January — February 2011 protests, police brutality was high in response to the protests. Jack Shenker, a reporter for The Guardian, was arrested during the mass protests in Cairo on 26 January 2011. He witnessed fellow Egyptian protesters being tortured, assaulted, and taken to undisclosed locations by police officers. Shenker and other detainees were released after one of his fellow detainees' well-known father, Ayman Nour, covertly intervened.[73][74][75]

Corruption in government elections[edit]

Corruption, coercion to not vote, and manipulation of election results occurred during many of the elections over 30 years.[76] Until 2005, Mubarak was the only candidate to run for the presidency, on a yes/no vote.[77] Mubarak won five consecutive presidential elections with a sweeping majority. Opposition groups and international election monitoring agencies accused the elections of being rigged. These agencies have not been allowed to monitor the elections. The only opposing presidential candidate in recent Egyptian history, Ayman Nour, was imprisoned before the 2005 elections.[78] According to a 2007 UN survey, voter turnout was extremely low (around 25%) because of the lack of trust in the corrupt representational system.[79]

Demographic and economic challenges[edit]

- Unemployment and reliance on subsidized goods

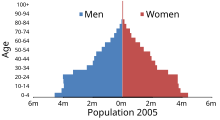

The population of Egypt grew from 30,083,419 in 1966[80] to roughly 79,000,000 by 2008.[81] The vast majority of Egyptians live in the limited spaces near the banks of the Nile River, in an area of about 40,000 square kilometers (15,000 sq mi), where the only arable land is found. In late 2010 around 40% of Egypt's population of just under 80 million lived on the fiscal income equivalent of roughly US$2 per day, with a large part of the population relying on subsidized goods.[1]

According to the Peterson Institute for International Economics and other proponents of demographic structural approach (cliodynamics), a basic problem in Egypt is unemployment driven by a demographic youth bulge: with the number of new people entering the job force at about 4% a year, unemployment in Egypt is almost 10 times as high for college graduates as it is for people who have gone through elementary school, particularly educated urban youth—the same people who were out in the streets during the revolution.[82][83]

- Poor living conditions and economic conditions

Egypt's economy was highly centralised during the tenure of President Gamal Abdel Nasser but opened up considerably under President Anwar Sadat and Mubarak. From 2004 to 2008 the Mubarak-led government aggressively pursued economic reforms to attract foreign investment and facilitate GDP growth, but postponed further economic reforms because of global economic turmoil. The international economic downturn slowed Egypt's GDP growth to 4.5% in 2009. In 2010 analysts said the government of Prime Minister Ahmed Nazif would need to restart economic reforms to attract foreign investment, boost growth, and improve economic conditions. Despite high levels of national economic growth over the past few years, living conditions for the average Egyptian remained poor,[84] though better than many other countries in Africa.[82]

Corruption among government officials[edit]

Political corruption in the Mubarak administration's Ministry of Interior rose dramatically due to the increased level of control over the institutional system necessary to prolong the presidency.[85] The rise to power of powerful businessmen in the NDP, in the government, and in the People's Assembly led to massive waves of anger during the years of Prime Minister Ahmed Nazif's government. An example is Ahmed Ezz's monopolising the steel industry in Egypt by holding more than 60% of the market share.[86] Aladdin Elaasar, an Egyptian biographer and an American professor, estimated that the Mubarak family was worth from $50 to $70 billion.[87][88]

The wealth of Ahmed Ezz, the former NDP Organisation Secretary, was estimated to be 18 billion Egyptian pounds;[89] the wealth of former Housing Minister Ahmed al-Maghraby was estimated to be more than 11 billion Egyptian pounds;[89] the wealth of former Minister of Tourism Zuhair Garrana is estimated to be 13 billion Egyptian pounds;[89] the wealth of former Minister of Trade and Industry, Rashid Mohamed Rashid, is estimated to be 12 billion Egyptian pounds;[89] and the wealth of former Interior Minister Habib al-Adly was estimated to be 8 billion Egyptian pounds.[89]

The perception among Egyptians was that the only people to benefit from the nation's wealth were businessmen with ties to the National Democratic Party; "wealth fuels political power and political power buys wealth."[90]

During the Egyptian parliamentary election, 2010, opposition groups complained of harassment and fraud perpetrated by the government. Opposition and civil society activists called for changes to a number of legal and constitutional provisions which affect elections.[citation needed]

In 2010, Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) report assessed Egypt with a CPI score of 3.1, based on perceptions of the degree of corruption from business people and country analysts (with 10 being clean and 0 being totally corrupt).[91]

Lead-up to the protests[edit]

To prepare for a possible overthrow of Mubarak, opposition groups studied the work of Gene Sharp on non-violent revolution and worked with leaders of Otpor!, the student-led Serbian uprising of 2000. Copies of Sharp's list of 198 non-violent "weapons", translated into Arabic and not always attributed to him, were circulated in Tahrir Square during its occupation.[92][93]

Tunisian revolution[edit]

After the ousting of Tunisian president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali due to mass protests, many analysts, including former European Commission President Romano Prodi, saw Egypt as the next country where such a revolution might occur.[94] The Washington Post commented, "The Jasmine Revolution [...] should serve as a stark warning to Arab leaders – beginning with Egypt's 83-year-old Hosni Mubarak – that their refusal to allow more economic and political opportunity is dangerous and untenable."[95] Others held the opinion that Egypt was not ready for revolution, citing little aspiration of the Egyptian people, low educational levels, and a strong government with the support of the military.[96] The BBC said, "The simple fact is that most Egyptians do not see any way that they can change their country or their lives through political action, be it voting, activism, or going out on the streets to demonstrate."[97]

Self-immolation[edit]

Following the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi in Tunisia on 17 December, a man set himself ablaze on 17 January in front of the Tunisian parliament;[98] and about five more attempts of self-immolation followed.[96]

National Police Day protests[edit]

Opposition groups planned a day of revolt for 25 January, coinciding with the National Police Day. The purpose was to protest against abuses by the police in front of the Ministry of Interior.[99] These demands expanded to include the resignation of the Minister of Interior, an end to State corruption, the end of Egyptian emergency law, and term limits for the president.

Many political movements, opposition parties, and public figures supported the day of revolt, including Youth for Justice and Freedom, Coalition of the Youth of the Revolution, the Popular Democratic Movement for Change, the Revolutionary Socialists and the National Association for Change. The April 6 Youth Movement was a major supporter of the protest and distributed 20,000 leaflets saying "I will protest on 25 January to get my rights". The Ghad El-Thawra Party, Karama, Wafd and Democratic Front supported the protests. The Muslim Brotherhood, Egypt's largest opposition group,[100] confirmed on 23 January that it would participate.[100][101] Public figures including novelist Alaa Al Aswany, writer Belal Fadl, and actors Amr Waked and Khaled Aboul Naga announced they would participate. However, the leftist National Progressive Unionist Party (the Tagammu) stated it would not participate. The Coptic Church urged Christians not to participate in the protests.[100]

Twenty-six-year-old Asmaa Mahfouz was instrumental[102] in sparking the protests.[103] In a video blog posted a week before National Police Day,[104] she urged the Egyptian people to join her on 25 January in Tahrir Square to bring down Mubarak's regime.[105] Mahfouz's use of video blogging and social media went viral[106] and urged people not to be afraid.[107] The Facebook group set up for the event attracted 80,000 attendees.

Timeline[edit]

|

|

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2011) |

From King Farouk to Mubarak[edit]

All causes attached to the 2011's Egyptian Revolution against Mubarak existed in 1952, when the Free Officers ousted King Farouk.[108] Inheritance of Crown, corruption, under-development, unemployment,unfair distribution of wealth, and the threat of Israel to the Egyptian national security. Only one new cause that could explain the new Arab Spring is the population explosion and the severe unemployment of great percentage of the population.

- The first signal that paved the road to Mubarak was the 1967's war between Egypt and Israel that was caused by Naser's appointments of incompetent officers in all branches of the Egyptian military and intelligence.

- Naser's defeat in 1967 accelerated his death and brought Anwar Sadat to power in 1970. Hence, Sadat undid all social reforms advanced by Naser in his struggle with manipulation of the Soviets to his needs for military assistance. In fact, Sadat predicted the collapse of the Soviet communist bloc two decades before its occurrence.

- As Sadat neglected all major steps to modernize Egypt and contented his cronies with selling desert lands and importing goods, Egypt suffered serous decline in infrastructure industries that could generate new jobs.

- The death of Sadat in 1981, left a heavy load to Hosni Mubarak to manage. With total lack of academic or governmental experience, Mubarak implemented the emergency rule throughout his 30-year rule and refrained from appointing a vice president until he was pressed to step down.

- The communication factors such as the Internet, cell phones, and satellite TV channels, thought to contribute greatly to igniting the revolution,one cannot ignore the role of the mosques and Friday prayers that existed over many centuries and played major roles in changing governments. Not only that the mosques brought the Muslim Brothers to power, but also that the Muslim Brothers imposed threats on all governments from 1928 throughout 2011, as it still does in countries neighboring to Egypt.[109]

Under Hosni Mubarak's rule[edit]

25 January 2011: The "Day of Revolt": Protests erupted throughout Egypt, with tens of thousands of protesters gathered in Cairo and thousands more in cities throughout Egypt. The protests targeted President Hosni Mubarak's government, and mostly adhered to non-violence. There were some reports of civilian and police casualties.

26 January 2011:civil unrest in Suez and various other areas throughout Egypt. Police seize many activists.

28 January 2011: The "Friday of Anger" protests began. Hundreds of thousands demonstrated in Cairo and other Egyptian cities after Friday prayers. Opposition leader Mohamed ElBaradei arrived in Cairo. There were reports of looting. Prisons were opened and burned down, allegedly on orders from then-Minister of the Interior Habib El Adly. Prison inmates escaped en masse, in what was believed to be an attempt to terrorise protesters. Police forces were withdrawn from the streets, and the military was deployed. International fears of violence grew, but no major casualties were reported. President Hosni Mubarak made his first address to the nation and pledged to form a new government. Later that night clashes broke out in Tahrir Square between revolutionaries and pro-Mubarak demonstrators, leading to the injury of several and the death of some.

29 January 2011: The military presence in Cairo increased. A curfew was declared, but was widely ignored as the flow of defiant protesters to Tahrir Square continued throughout the night. The military reportedly refused to follow orders to fire live ammunition, and exercised restraint overall. There were no reports of major casualties. On 31 January, Israeli media reported that the 9th, 2nd, and 7th Divisions of the Egyptian Army had been ordered into Cairo to help restore order.[110]

1 February 2011: Mubarak made another televised address and offered several concessions. He pledged to not run for another term in the elections planned for September, and pledged political reforms. He stated he would stay in office to oversee a peaceful transition. Small but violent clashes began that night between pro-Mubarak and anti-Mubarak groups.

2 February 2011: "Incident of the Camel". Violence escalated as waves of Mubarak supporters met anti-government protesters, and some Mubarak supporters rode on camels and horses into Tahrir Square, reportedly wielding sticks. President Mubarak reiterated his refusal to step down in interviews with several news agencies. Incidents of violence toward journalists and reporters escalated amid speculation that the violence was being encouraged by Mubarak as a way to bring the protests to an end.

6 February 2011: A multifaith Sunday Mass was held with Egyptian Christians and Egyptian Muslims in Tahrir Square. Negotiations involving Egyptian Vice President Omar Suleiman and representatives of the opposition commenced amid continuing protests throughout the nation. The Egyptian army assumed greater security responsibilities, maintaining order and guarding The Egyptian Museum of Antiquity. Suleiman offered reforms, while others of Mubarak's regime accused foreign nations, including the US, of interfering in Egypt's affairs.

10 February 2011: Mubarak formally addressed Egypt amid speculation of a military coup, but rather than resigning (as was widely expected), he simply stated he would delegate some of his powers to Vice President Suleiman, while continuing as Egypt's head of state. Reactions to Mubarak's statement were marked by anger, frustration and disappointment, and throughout various cities there was an escalation of the number and intensity of demonstrations.

11 February 2011: The "Friday of Departure": Massive protests continued in many cities as Egyptians refused the concessions announced by Mubarak. Finally, at 6:00 pm local time, Suleiman announced Mubarak's resignation, entrusting the Supreme Council of Egyptian Armed Forces with the leadership of the country. Nationwide celebrations immediately followed.

Post-revolution timeline[edit]

Under Supreme Council of the Armed Forces[edit]

13 February 2011: The Supreme Council dissolved Egypt’s parliament and suspended the Constitution in response to demands by demonstrators. The council declared that it would hold power for six months, or until elections could be held. Calls were made for the council to provide more details and specific timetables and deadlines. Major protests subsided but did not end. In a gesture to a new beginning, protesters cleaned up and renovated Tahrir Square, the epicenter of the demonstrations, although many pledged they would continue protests until all the demands had been met.

17 February 2011: The army stated it would not field a candidate in the upcoming presidential elections.[111] Four important figures of the former regime were detained on that day: former interior minister Habib el-Adly, former minister of housing Ahmed Maghrabi former tourism minister Zuheir Garana, and steel tycoon Ahmed Ezz.[112]

2 March 2011: The constitutional referendum was tentatively scheduled for 19 March 2011.[113]

3 March 2011: A day before large protests against him were planned, Ahmed Shafik stepped down as Prime Minister and was replaced by Essam Sharaf.[114]

5 March 2011: Several State Security Intelligence (SSI) buildings were raided across Egypt by protesters, including the headquarters for Alexandria Governorate and the main national headquarters in Nasr City, Cairo. Protesters stated they raided the buildings to secure documents they believed to show various crimes committed by the SSI against the people of Egypt during Mubarak's rule.[115][116]

6 March 2011: From the Nasr City headquarters, protesters acquired evidence of mass surveillance and vote rigging, and noted rooms full of videotapes, piles of shredded and burned documents, and cells where activists recounted their experiences of detention and torture.[117]

19 March 2011: The constitutional referendum was held and passed by 77.27%.[118]

22 March 2011: Parts of the Interior Ministry building caught fire during police demonstrations outside.[119]

23 March 2011: The Egyptian Cabinet orders a law criminalising protests and strikes that hampers work at private or public establishments. Under the new law, anyone organising or calling for such protests will be sentenced to jail and/or a fine of LE500,000 (~100,000 USD).[120]

1 April 2011: The "Save the Revolution" day: Approximately four thousand demonstrators filled Tahrir Square for the largest protest in weeks, demanding that the ruling military council move faster to dismantle lingering aspects of the old regime.[121] Protestors demanded trial for Hosni Mubarak, Gamal Mubarak, Ahmad Fathi Sorour, Safwat El-Sherif and Zakaria Azmi as well.

8 April 2011: The "Friday of Cleaning": Hundreds of thousands of demonstrators again filled Tahrir Square, criticizing the ruling Supreme Council of the Armed Forces for not following through on revolutionary demands. They demanded the resignation of remaining regime figures and the removal of Egypt’s public prosecutor due to the slow pace of investigations of corrupt former officials.[122]

7 May 2011: 2011 Imbaba church attacks in which Salafi Muslims undertook a series of attacks against Coptic Christian churches in the poor working-class neighborhood of Imbaba in Cairo.[123]

27 May 2011: The "Second Friday of Anger" (a.k.a. "Second Revolution of Anger" or "The Second Revolution"): Tens of thousands of demonstrators filled Tahrir Square in Egypt's capital Cairo,[124] besides perhaps demonstrators in each of Alexandria, Suez, Ismailia, Gharbeya and other areas; in the largest demonstrations since ousting Mubarak's Regime. Protestors demanded no military trials for civilians, the Egyptian Constitution to be made before the Parliament elections and for all members of the old regime and those who killed protestors in January and February to be put on fair trial.

1 July 2011: The "Friday of Retribution"; Hundreds of thousands of protesters gathered in Suez, Alexandria and Tahrir Square in Cairo, to voice frustration with the ruling Supreme Council of the Armed Forces for what they called the slow pace of change five months after the revolution, some also feared that the military is to rule Egypt indefinitely.[125]

8 July 2011: The "Friday of Determination"; Hundreds of thousands of protesters gathered in Suez, Alexandria and Tahrir Square in Cairo. They demanded immediate reforms and swifter prosecution of former officials from the ousted government.[126]

15 July 2011: Hundreds of thousands continue to protest in Tahrir Square.

23 July 2011: Thousands of protesters try to march to the Defense Ministry. They are met with thugs that have sticks, stones, molotov cocktails and other things. The protests were set off by a speech by Mohammed Tantawi commemorating the 1952 military coup.

1 August 2011: Egyptian soldiers clash with protesters, tearing down tents. Over 66 people were arrested. Most Egyptians supported the military's action.[citation needed]

6 August 2011: Hundreds of protesters gathered and prayed in Tahrir Square. After they were done, they were attacked by the military.[127]

9 September 2011: The "2011 Israeli embassy attack"; The"Friday of Correcting the Path"; Tens of thousands of people protested Suez, Alexandria, Cairo, and other cites. Islamist protesters were absent.

9 October 2011: The "Maspero demonstrations";[128][129] Late into the evening of 9 October, during a protest that was held in Maspiro,[130] peaceful Egyptian protesters, calling for the dissolution the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, the resignation of its chairman, Field Marshal Mohamed Tantawi, and the dismissal of the governor of Aswan province, were attacked by military police. At least 25 people[131] were killed and more than 200 wounded.

19 November 2011: Clashes first erupt in Tahrir Square as demonstrators reoccupy the location in central Cairo. Central Security Forces deploy tear gas in an attempt to control the situation.[132]

20 November 2011: Police forces attempt to forcibly clear the square, but protesters soon return in more than twice their original numbers. Fierce fighting breaks out and continues through the night, with the police again using tear gas, beating and shooting demonstrators.[132]

21 November 2011: Demonstrators return to the square, with Coptic Christians standing guard as Muslims protesting the regime pause for prayers. The Health Ministry says at least 23 have died and over 1,500 have been wounded since 19 November.[132] Solidarity protests are held in Alexandria, Suez, and at least five other major Egyptian cities.[133] Dissident journalist Hossam el-Hamalawy tells Al Jazeera that Egyptians will launch a general strike because they have "had enough" of the SCAF.[134]

28 November 2011 – 11 January 2012: Egyptian parliamentary election

23 January 2012: Democratically elected representatives of the People’s Assembly met for the first time since Egypt’s revolution, and the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces transferred legislative authority to them.[135][136][137]

24 January 2012: Military ruler Field Marshal Hussein Tantawi said the decades-old state of emergency will be lifted partially on Wednesday 25 January.[138][139][140][141]

12 April 2012: An administrative court suspended the 100-member constitutional assembly tasked with drafting a new constitution for Egypt.[142][143][144]

23 and 24 May 2012: First round of voting in Egypt's first presidential election after Hosni Mubarak was deposed by the Egyptian revolution.

31 May 2012: The decades-old state of emergency expired and with it Egypt's emergency law has been lifted completely.[145][146]

2 June 2012: Former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak and his former interior minister Habib al-Adli were convicted to life on prison on the basis of their failure to stop the killings during the first six days of the 2011 Egyptian revolution. The former president, his two sons and a business tycoon were acquitted of corruption charges because a statute of limitations had expired. Six senior police officials were also acquitted for their role in the killings of demonstrators due to lack of evidence.[147][148][149][150]

8 June 2012: Political factions in Egypt have tentatively agreed to a deal to form a new constitutional assembly consisting of 100 members which will draft the country's new constitution.[151]

12 June 2012: Members of Egypt's parliament have met to vote for members of a constitutional assembly, but dozens of secular MPs walked out of the session, accusing Islamist parties of trying to dominate the new panel.[152]

13 June 2012: After Egypt's military-led government imposed a de facto martial law, extending the arrest powers of security forces, Egypt's Justice Ministry issued a decree granting military officers the authority to arrest civilians and to try them in military courts.[153][154][155][156] The provision remains in effect until a new constitution is introduced, and could mean those detained could remain in jail for that long according to state-run Egy News.[157]

14 June 2012: The Egyptian Supreme Constitutional Court found that a law passed by parliament in May banning former regime figures from running for office was unconstitutional, thereby ending a threat to Ahmed Shafik's candidacy for president during Egypt's 2012 presidential election. Shafik was thus able stay in the presidential race. The Court also judged that all articles making up the law that regulated the 2011 parliamentary elections were invalid, thereby upholding a ruling by a lower court which found that the elections had been conducted illegally when candidates running on party slates were allowed to contest the one-third of Parliamentary seats that had been set aside for independents. The consequence of the Supreme Constitutional Court ruling was that the Egyptian parliament had to be dissolved immediately. In response to this, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces resumed full legislative authority. In addition the SCAF explained that it will announce a 100-person assembly that will write the country's new constitution after the parliament failed to agree on a committee to write a new constitution defining the powers of the president and the parliament.[157][158][159][160][161]

15 June 2012: The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces formally dissolved Parliament and security forces were stationed around the building on orders to bar anyone, including lawmakers, from entering the chambers without official notice.[162][163]

16 and 17 June 2012: Second round of voting in Egypt's first presidential election after Hosni Mubarak was deposed by the Egyptian revolution. Egypt's military rulers issued an interim constitution[164][165][166][167][168][169][170][171] granting themselves the power to control the prime minister, lawmaking, the national budget, and declarations of war, without any supervision or oversight. They also picked a 100-member panel to draft a permanent constitution.[163][172] Among the powers of the president are the powers to choose his vice presidents and cabinet, to propose the state budget and laws and to issue pardons.[167] The interim constitution also removed the military and the defense minister from presidential authority and oversight.[155][167] Under the terms of the interim constitution the permanent constitution must be written within three months and shall then within 15 days be subject to a public referendum. Once the permanent constitution has been approved a new parliament election shall be held within a month to replace the dissolved one.[165][166][167][168]

18 June 2012: Egypt's military rulers declared that they picked a 100-member panel to draft a permanent constitution,[163] if a court case should strike down the parliament-picked assembly. They also promised a grand celebration at the end of June to mark their formal handover to the new president.[155][173] Muslim Brotherhood candidate Mohamed Morsi declared himself the winner of the presidential election.[165][166]

19–24 June: Egyptians assemble in Tahrir Square to 1.) protest against Egypt's military council which dissolved a new, democratically elected, Islamist-led parliament and assumed legislative power on the eve of the presidential run-off and then issued an interim constitutional declaration as polls closed setting strict limits on the powers of whoever would be elected president, and 2.) await the outcome of the 2012 Egyptian presidential election.[174][175][176][177][178][179][180]

24 June 2012: Muslim Brotherhood candidate Mohamed Morsi is declared winner of Egypt's first free presidential election since the ouster of Hosni Mubarak by Egypt’s electoral commission and is the first Islamist elected to be head of an Arab state.[181][182][183][184][185][186]

26 June 2012: Egypt's Supreme Administrative Court issued a decision to revoke Decree No. 4991/2012 of the Minister of Justice that granted military intelligence and military police judicial powers to arrest civilians, a right previously reserved for civilian police officers.[172][187][188][189]

27–28 June 2012: After the first Constituent Assembly of Egypt was declared unconstitutional and dissolved in April by Egypt's Supreme Administrative Court, Egypt's second constituent assembly met to establish framework for drafting first post-Mubarak constitution with threat of dissolution by court order still hanging over it.[190][191]

29 June 2012: Mohamed Morsi took a symbolic oath of office in a packed Tahrir Square declaring that the people are the source of power which they grant and withdraw.[192][193][194]

30 June 2012: Mohamed Morsi was sworn in as Egypt's first democratically elected president before judges at the Supreme Constitutional Court, delivered, from the podium used by U.S. President Barack Obama to reach out to the Islamic world in 2009 during the A New Beginning speech, a speech before the lawmakers of the dissolved Parliament, the ruling generals and foreign ambassadors in the Grand Hall of Cairo University and attended later at a ceremony hold at a desert army base outside Cairo, Heikstep army base, in which the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces formally handed power over to Mursi.[195][196][197][198][199]

Under President Mohamed Morsi[edit]

For a chronological summary of the major events which took place after the 2011–2012 Egyptian revolution under President Mohamed Morsi see Timeline of the 2011–2012 Egyptian revolution (Post-revolution timeline).

November 2012 declaration[edit]

On 22 November 2012, Morsi issued a declaration immunizing his decrees from challenge and seeking to protect the work of the constituent assembly drafting the new constitution.[200] The declaration also requires a retrial of those accused in the Mubarak-era killings of protesters, who had been acquitted, and extends the mandate of the constituent assembly by two months. Additionally, the declaration authorizes Morsi to take any measures necessary to protect the revolution. Liberal and secular groups walked out of the constitutional constituent assembly because they believed that it would impose strict Islamic practices, while Muslim Brotherhood backers threw their support behind Morsi.[201]

The move was criticized by Mohamed ElBaradei, the leader of Egypt's Constitution Party, who said Morsi had "usurped all state powers and appointed himself Egypt's new pharaoh".[202][203] The move has led to massive protests and violent action throughout Egypt,[204] with protesters again erecting tents in Tahir Square, the site of the protests preceding the resignation of Hosni Mubarak. The protesters demanded a reversal of the declaration and the dissolution of the constituent assembly. Those gathered in the square called for a "huge protest" on Tuesday, 27 November.[205] Clashes were reported between protesters and police.[206] The declaration was also condemned by human rights groups such as Amnesty International UK.[207]

In April 2013, a youth group was created to register opposition to President Mohamed Morsi of Egypt and force him to call for early presidential elections by aiming to collect 15 million signatures by 30 June 2013 (which is the same date that he was sworn into office in 2012). That helped erupt the June 2013 protests. Although protests were scheduled for the 30 June, a fair number of people gathered from the 28th.[208] Advocates of Morsi (mainly of Islamic parties) also protested on the same day.[209] On the 30th, the group managed to organize massive protests in Al- Tahrir Square and the Presidential Palace which later spread to the different governorates demanding early presidential elections.[210] These protests are considered to be the largest protests in Egypt to date.[211] The people in favor of Morsi continued protesting, although outnumbered by those against him.

Second transitional period[edit]

Morsi was removed from office by the Egyptian Armed Forces in a coup d'état on 3 July 2013, as the military sided with protesters against Morsi's rule and the influence of the Muslim Brotherhood on Egyptian politics. However, unlike after the ouster of Hosni Mubarak in 2011, the head of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, Abdul Fatah al-Sisi, declared a civilian — senior jurist Adly Mansour — interim president of the country, with the right to issue constitutional declarations, and vested executive power in the Supreme Constitutional Court, making the interim president with Executive, Judicial and Constitutional powers, instead of declaring martial law.[212] Despite Mansour's installation as president, the military continued to exercise broad authority in cracking down on pro-Morsi demonstrations and riots. Clashes in some areas were deadly. Morsi refused to accept his removal from power, and many of his supporters vowed to restore him to office.[213]

Protests in cities and regions[edit]

- Cairo

Cairo has been at the epicentre of much of the crisis. The largest protests were held in downtown Tahrir Square, which was considered the "protest movement’s beating heart and most effective symbol."[214] On the first three days of the protests, there were clashes between the central security police and protesters and on 28 January, police forces withdrew from all of Cairo. Citizens formed neighbourhood watch groups to keep the order as widespread looting was reported. Traffic police were reintroduced to Cairo on the morning of 31 January.[215] An estimated 2 million people protested at Tahrir square. During the protest, reporters Natasha Smith, Lara Logan, and Mona Eltahawy were sexual assaulted while covering the events of the protest.[216][217][218][219]

- Alexandria

Alexandria, the home of Khaled Saeed, had major protests and clashes with the police. A demonstration on 3 February was reported to include 750,000 people.[citation needed] There were few confrontations as not many Mubarak supporters were around, except in occasional motorised convoys escorted by police. The breakdown of law and order, including the general absence of police on the streets, continued through to at least the evening of 3 February, including the looting and burning of one the country's largest shopping centres, Carrefour[citation needed] Alexandria protests were notable for the presence of Christians and Muslims jointly taking part in the events following the church bombing on 1 January, which saw street protests denouncing Mubarak's regime following the attack.

- Mansoura

In the northern city of Mansoura there were protests against the Mubarak regime every day from 25 January onwards.On 27 January, Mansoura was dubbed a "War Zone". On 28 January 13 were reported dead in violent clashes. On 9 February 18 more protesters had died. One protest on 1 February was estimated at one million people, The remote city of Siwa had been relatively calm.[220] Local sheikhs, who were reportedly in control of the community, put the community under lockdown after a nearby town was "torched."[221]

- Suez

The city of Suez has seen violent protests. Eyewitness reports have suggested that the death toll there may be high, although confirmation has been difficult due to a ban on media coverage in the area.[222] Some online activists referred to Suez as Egypt's Sidi Bouzid, the Tunisian city where protests started.[223] A labour strike was held on 8 February.[224] Large protests took place on 11 February.[225]

On 3 February, 4,000 protesters went to the streets to call for Mubarak's departure.[226]

- Protests in Other Cities

There were also protests in Luxor.[227] On 11 February, Police opened fire on protesters in Dairut, tens of thousands of protesters took to the streets of Shebin el-Kom, thousands protested in the city of El-Arish, in the Sinai Peninsula,[225] large protests took place in the southern city of Sohag and Minya, and nearly 100,000 people protested in and about the local government headquarters in Ismaïlia.[225] Over 100,000 protesters gathered on 27 January in front of the city council in Zagazig.[228] Bedouins in the Sinai Peninsula fought security forces for several weeks.[229] As a result of the decrease in military forces on the borders, Bedouin groups protected the borders and pledged their support to the ongoing revolution.[230] No protests or civil unrest took place in Sharm-El-Sheikh on 31 January.[231]

Deaths[edit]

Leading up to the protests, six cases of self-immolation were reported, including a man arrested while trying to set himself on fire in downtown Cairo.[232] These cases were inspired by, and began exactly one month after, the acts of self-immolation in Tunisia triggering the 2010–2011 Tunisian uprising. The self-immolated included Abdou Abdel-Moneim Jaafar,[233] Mohammed Farouk Hassan,[234] Mohammed Ashour Sorour,[235] and Ahmed Hashim al-Sayyed who later died from his injuries.[236]

As of 30 January, Al Jazeera reported as many as 150 deaths in the protests.[237] The Sun reported that the dead could include at least 10 policemen, 3 of whom were killed in Rafah by "an enraged mob".[238]

By 29 January 2000 people were known to be injured.[239] The same day, an employee of the Azerbaijani embassy in Egypt was killed while returning home from work in Cairo;[240] the next day Azerbaijan sent a plane to evacuate citizens[241] and opened a criminal investigation into the death.[242]

Funerals for the dead on the "Friday of Anger" were held on 30 January. Hundreds of mourners gathered for the funerals calling for Mubarak's removal.[243] By 1 February, the protests had left at least 125 people dead,[244] although Human Rights Watch said that UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay claimed that as many as 300 people may have died in the unrest. This unconfirmed tally included 80 Human Rights Watch-verified deaths at two Cairo hospitals, 36 in Alexandria, and 13 in the port city of Suez, among others;[245][246][247] over 3,000 people were also reported as injured.[245][247]

An Egyptian Governmental Fact-Finding mission Known as "Fact-Finding National commission About 25 Jan Revolution" announced on 19 April that at least 846 Egyptians died in the nearly three-week long popular uprising.[248][249][250] One of the more prominent Egyptians killed was Emad Effat, a senior official of Egypt’s Dar al-Ifta department of al-Azhar that issues Islamic fatwas. He died 16 December 2011 after being shot in front of the cabinet building.[251] At his funeral the next day, hundreds of mourners chanted "Down with military rule."[251][252]

International reactions[edit]

International response to the protests was initially mixed,[253] though most called for peaceful actions on both sides and move towards reform. Most Western governments expressed concern about the situation. Many governments issued travel advisories and made attempts to evacuate their citizens from the country.[254]

The European Union's Foreign Affairs Chief issued a statement saying "I also reiterate my call upon the Egyptian authorities to urgently establish a constructive and peaceful way to respond to the legitimate aspirations of Egyptian citizens for democratic and socioeconomic reforms."[255] The United States, Britain, France, Germany and others issued similar statements calling for reforms and an end to violence against peaceful protesters. Many states in the region expressed concern and supported Mubarak, in particular Saudi Arabia, which issued a statement saying it "strongly condemned" the protests,[256] while others, like Tunisia and Iran, supported the protests. Israel was most cautious for a change, with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu asking his government ministers to maintain silence, and urging Israel's US and European allies to curb their criticism of President Mubarak;[257][258] however, an Arab-Israeli parliamentarian supported the protests. There were also numerous solidarity protests for the anti-government protesters around the world.

NGOs also expressed concern about the protests and the ensuing heavy-handed state response. Amnesty International described attempts to discourage protests as "unacceptable".[259] Many countries also issued travel warnings or began evacuating their citizens, including the US, Israel, Great Britain, and Japan. Even multinational corporations began evacuating their expatriate workers.[260] Many university students were also evacuated.

Post-ousting[edit]

Many nations, leaders, and organizations hailed the end of the Mubarak regime. There were celebrations in Tunisia, and Lebanon. World leaders including Angela Merkel and David Cameron joined in praising the Revolution.[261] United States President Barack Obama praised the achievement of the Egyptian people and encouraged other activists by saying "let's look at Egypt's example"[262] Amid the growing concerns for the country, on 21 February, David Cameron, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, became the first world leader to visit Egypt since Mubarak was ousted as the president 10 days previously. A news blackout was lifted as the prime minister landed in Cairo for a brief five-hour stopover hastily added at the start of a planned tour of the Middle East.[263] On 15 March United States Secretary of State Hillary Clinton visited Egypt, she was the highest ranking US official to visit Egypt after the handover of power from Mubarak to the military. Clinton urged the military leaders to begin the process of a democratic transition and offer support to those who had been protesting, as well as reaffirming ties between the two nations.[264]

Results[edit]

On 29 January, Mubarak indicated he would be changing the government because despite a "point of no return" being crossed, national stability and law and order must prevail, that he had requested the government, formed only months ago, to step down, and that a new government would be formed.[265] He then appointed Omar Suleiman, head of Egyptian Intelligence, as vice president and Ahmed Shafik as prime minister.[266] On 1 February, he spoke again saying he would stay in office until the next election in September 2011 and then leave without standing as a candidate. He also promised to make political reforms. He made no offer to step down.

The Muslim Brotherhood joined the revolution on 30 January, calling on all opposition groups to unite against Mubarak, and for the military to intervene. They joined other opposition groups in electing Mohammed el Baradei to lead a National Salvation Government in the interim period.[267]

Many of Al-Azhar Imams joined the protesters on 30 January all over the country.[268] Christian leaders asked their congregations to stay away from protests, though a number of young Christian activists joined the protests led by Wafd Party member Raymond Lakah.[269]

On 31 January, Mubarak swore in his new cabinet in the hope that the unrest would fade. The protesters did not leave and continued to demonstrate in Cairo's Tahrir Square to demand the downfall of Mubarak. The vice-president and the prime minister were already appointed.[270] He told the new government to preserve subsidies, control inflation and provide more jobs.[271]

On 1 February, Mubarak said he never intended to run for reelection[272] in the upcoming September presidential election, though his candidacy had previously been announced by high-ranking members of his National Democratic Party[273]

In his speech, he asked parliament for reforms:

According to my constitutional powers, I call on parliament in both its houses to discuss amending article 76 and 77 of the constitution concerning the conditions on running for presidency of the republic and it sets specific a period for the presidential term. In order for the current parliament in both houses to be able to discuss these constitutional amendments and the legislative amendments linked to it for laws that complement the constitution and to ensure the participation of all the political forces in these discussions, I demand parliament to adhere to the word of the judiciary and its verdicts concerning the latest cases which have been legally challenged.

—Hosni Mubarak, 1 February 2011[274]

Various opposition groups, including the Muslim Brotherhood (MB), reiterated demands for Mubarak's resignation. The MB also said, after protests turned violent, that it was time for the military to intervene.[275] Mohammed ElBaradei, who said he was ready to lead a transitional government,[276] was also the consensus candidate by a unified opposition including: the 6 April Youth Movement, We Are All Khaled Said Movement, National Association for Change, 25 January Movement, Kefaya and the Muslim Brotherhood.[277] ElBaradei formed a "steering committee".[278] On 5 February, a "national dialogue" was started between the government and opposition groups to work out a transitional period before democratic elections.

The Egyptian state cracked down on the media, and shut down internet access,[279] a primary means of communication for the opposition. It is important to note that this was done with the help of London-based company Vodafone, among others.[280][281][282] Journalists were also harassed by the regime's supporters, eliciting condemnation from the Committee to Protect Journalists, European countries and the United States.

Further, American company Narus, a subsidiary of Boeing Corporation, sold the Mubarak government with surveillance equipment that helped identify dissidents.[283]

Reform process[edit]

The revolution's main demands chanted over and over in every protest are: Bread [livelihood], Freedom, Social Justice, Human Dignity. Fulfillment of these demands has been uneven and debatable.

Some demands stemming form the main four demands stated earlier, includes the following:

| Demand | Status | Date |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Resignation of President Mohammed Hosni Mubarak. | Met. | 11 February 2011 |

| 2. Setting a new minimum wage and setting a maximum wage. | Not met. | |

| 3. Canceling the State of Emergency (colloquially referred to as "The Emergency Law"). | Met.[285] | 31 May 2012 |

| 4. Dismantling the State Security Investigations Service. | Met.[286] | 31 May 2012 |

| 5. Announcement by (Vice-President) Omar Suleiman that he will not run in the next presidential elections. | Initially, claimed to be met.[287] (Later, promise broken in April 2012) |

3 February 2011 |

| 6. Dissolving the Parliament. | Met. | 13 February 2011 |

| 7. Release of all prisoners taken since 25 January. | Ongoing (more people have been arrested and faced Military trials since SCAF took over) | |

| 8. Ending of the recently imposed curfew. | Met.[288] | 15 June 2011 |

| 9. Removing the SSI-controlled university-police. | Claimed to be met. | 3 March 2011 |

| 10. Investigation of officials responsible for violence against protesters. | Ongoing. | |

| 11. Firing Minister of Information Anas el-Fiqqi and stopping government owned media propaganda. | Not met; minister fired, ministry still exists, and propaganda still ongoing[289] | |

| 12. Reimbursing shop owners for losses during the curfew | Announced but Not Met. | 7 February 2011 |

| 13. Announcing the demands above on government television and radio | Claims to be met. | 11–18 February 2011 |

| 14. Dissolving the NDP. | Met. | 16 April 2011 |

| 15. Arrest, Interrogation and Trial of (now-former) president Hosni Mubarak and his two sons: Gamal Mubarak and Alaa Mubarak. | Met; All ordered to stand trial. (Judiciary system is under SCAF control). On 2 June 2012, Hosni Mubarak was sentenced to life in prison for the death of at least some of the protesters.[290] | 24 May 2011 |

| 16. Transfer of power from the SCAF to a civilian-governed council. | Met.[291] | 30 June 2012 |

| 17. The resignation of Mohamed Morsy | Met. (Forced out after mass protests and army intervention) | 3 July 2013 |

On 17 February, an Egyptian prosecutor ordered the detention of three ex-ministers, former Interior Minister Habib el-Adli, former Tourism Minister Zuhair Garana and former Housing Minister Ahmed el-Maghrabi, and a prominent businessman, steel magnate Ahmed Ezz, pending trial on suspicion of wasting public funds. The public prosecutor also froze the accounts of Adli and his family members on accusations that over 4 million Egyptian pounds ($680,000) were transferred to his personal account by a head of a contractor company, while calling on the Foreign Minister to contact European countries and ask them to freeze the accounts of the defendants.[292]

Meanwhile, the United States announced on the same day that it was giving Egypt $150 million in crucial economic assistance to help it transition towards democracy following the overthrow of longtime president Mubarak. US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said that William Burns, the Under-secretary of State for political affairs, and David Lipton, a senior White House adviser on international economics, would travel to Egypt the following week.[292]

On 19 February, a moderate Islamic party, named (Arabic: حزب الوسط الجديد) Al-Wasat Al-Jadid, or the New Center Party, which was outlawed for 15 years was granted official recognition by an Egyptian court. The party was founded in 1996 by activists who split off from the Muslim Brotherhood and sought to create a tolerant Islamic movement with liberal tendencies, but its attempts to register as an official party were rejected four times since then. On the same day, Prime Minister Ahmed Shafiq said 222 political prisoners would be released. He said only a few were detained during the popular uprising and put the number of remaining political prisoners at 487, but did not say when they would be released.[293]

On 20 February, Dr. Yehia El Gamal a well known activist and law professor, announced (on TV channels) accepting a Vice Prime Minister position within the new government that will be announced on 21–22 February. He also announced the removal of many of the previous government members to alleviate the situation.

On 21 February, the Muslim Brotherhood announced it would form a political party for the upcoming parliamentary election, called the Freedom and Justice Party, which was to be led by Dr. Saad Ketatni.[294][295][296] Its spokesperson noted that "when we talk about the slogans of the revolution – freedom, social justice, equality – all of these are in the Sharia (Islamic law)."[297]

On 3 March, Prime Minister Shafik submitted his resignation to the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces. The Council appointed Essam Sharaf, a former Minister of Transport who began vocal criticism of the regime following his resignation, particularly after the Qalyoub rail accident in 2006, to replace Shafik and form a new government. Sharaf's appointment is seen as a significant concession to protesters, as he had been actively involved during the action at Tahrir Square.[298][299][300] Sharaf appointed former International Court of Justice judge Nabil Elaraby as Foreign Minister and General Mansour El Essawi as Interior Minister.[301][302]

On 16 April, the Higher Administrative Court dissolved the former ruling National Democratic Party (NDP) and ordered its funds and property to be handed over to the government.[303] On 24 May 2011, it was announced that Egypt's ousted President Hosni Mubarak and his two sons Gamal and Alaa are to be tried over the deaths of anti-government protesters in the revolution that began on 25 January.[304]

After-Revolution Freedom of Establishing Political Parties[edit]

Freedom was given to establish political parties only by "notifying" concerned authorities, resulting in establishing several political parties named after or in relation to the 25 January revolution. See List of political parties in Egypt.

Court trials of state officials accused of corruption[edit]

The ousting of Mubarak was followed by a series of arrests of, and / or imposed travel bans on high profile figures on charges of causing the death of 300–500 demonstrators, and the injury of 5,000 more, as well as charges of embezzlement, profiteering, money laundry, and abuse of human rights. Among these figures are Mubarak himself, his wife Suzanne Mubarak, his son Gamal, his son Alaa, the former Interior Minister Habib el-Adly, the former Housing Minister Ahmed El-Maghrabi, the former Tourism Minister Zoheir Garana and the former Secretary of the National Democratic Party for Organisational Affairs Ahmed Ezz.[305] Mubarak's ousting was also followed by widespread allegations of corruption against numerous other government officials and senior politicians[306][307] On 28 February 2011, Egypt's top prosecutor ordered an asset freeze for Mubarak and his family.[308] This was followed by arrest warrants, travel bans and judicial orders to freeze the assets of other known public figures, including the former Speaker of the Egyptian Parliament, Fathi Sorour, and the former Speaker of the Higher Legislative Body (Shura Council), Safwat El Sherif.[309][310] Arrest warrants were also issued against some public figures who left the country with the outbreak of the revolution. These warrants were issued on allegations of financial misappropriations, rather than human rights abuses. Among these public figures are Rachid Mohamed Rachid, the former Minister of Trade and Industry and Hussein Salem, a business tycoon. Salem is believed to have left for Dubai[311]

Trials of the accused officials started on 5 March 2011 when the former Interior Minster of Egypt, Habib el-Adli, appeared before the Giza Criminal Court in Cairo.[312] The trials of el-Adli and other public figures are expected to run a lengthy course.

In March 2011, following the revolution, Abbud al-Zumar, one of Egypt's most famous political prisoners, was freed after 30 years. He was founder and first emir of the Egyptian Islamic Jihad, and implicated in the assassination of President Anwar Sadat on 6 October 1981.[313]

On 24 May, former Egyptian President Mubarak was ordered to stand trial on charges of premeditated murder of peaceful protestors during the 2011 Egyptian revolution and, if convicted, could face the death penalty. The full list of charges released by the public prosecutor was "intentional murder, attempted killing of some demonstrators...misuse of influence and deliberately wasting public funds and unlawfully making private financial gains and profits."[12]

Analysis[edit]

Regional instability[edit]

The Egyptian Revolution, along with the events in Tunisia, sparked a wave of major uprisings. Demonstrations and protests have spread across the Middle East and North Africa. To date Algeria, Bahrain, Iran, Jordan, Libya, Morocco, Yemen, and Syria have all witnessed major protests. In addition, minor incidents have occurred in Iraq, Kuwait, Mauritania, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, and Sudan.

The protests in Egypt were not centred around religion-based politics, but nationalism and a broad-based social consciousness.[314] Before the uprising, the most organised and prominent opposition movements throughout the Arab world usually came from Islamist organisations that relied on a conviction of their faith, where members were motivated and ready to sacrifice. However, secular forces emerged from the revolution touting principles that religious groups shared with them: freedom, social justice, and dignity. Islamist organisations also emerged with greater freedom to operate. Although the cooperative, inter-faith revolution itself was no guarantee that partisan politics would not re-emerge in its wake, its success nonetheless represented a change from the intellectual stagnation created by decades of repression which simply pitted modernity and Islam against one another as conflicting and incompatible. Islamists and secularists both have been faced with new opportunities for dialogue and discourse, on matters such as the role of Islam and Sharia in society and freedom of speech, as well as the impact of secularism on a predominantly Muslim population.[315]

Despite the optimism surrounding the revolution, several commentators have expressed concerns about the risk of increased power and influence for Islamist forces in the country and the region at large, as well as the difficulties of integrating the different groups, ideologies, and visions for the country among the population. Journalist Caroline Glick argued that the Egyptian revolution portends a rise in religious radicalism and support for terrorism, citing a 2010 Pew Opinion poll which found that Egyptians support Islamists over modernizers by a ratio of over 2 to 1.[316] Journalist Shlomo Ben-Ami argued that Egypt's most formidable task is to refute the old paradigm of the Arab World that sees the only choices for regimes as between either repressive, secular dictatorships or repressive theocracies. He noted, however that with Islam such a central part of the society, any emergent regime is bound to be attuned to religion. In his view a democracy that excluded all religion from public life, as in France, could succeed in Egypt and no Arab democracy could disallow the participation of political Islam if it were to be genuine.[317]

Since the revolution Islamist parties such as the Muslim Brotherhood have shown unprecedented strength in the new more democratic landscape, taking leading roles in constitutional changes, voter mobilization, and protests.[318][319] This was a noted concern among the secular and youth movements, who wanted any elections to be held later rather than sooner, so that they might catch up with the already well-organized groups. Elections were held in September 2011 with the party of Liberty and Justice (the new-born party of the Muslim brotherhood) gaining 48.5% from correct votes in the elections. Although many claimed that this victory for the brotherhood means the control of religious party over Egypt, yet the youth movements and liberate parties pet on people's consciousness and that the normal tolerant people of Egypt wouldn't allow another Iran in Egypt.

Alexandria church bombing[edit]

Early on New Year's Day 2011 a bomb exploded in front of a church in Alexandria, killing 23 Coptic Christians. Egyptian officials said "foreign elements" were behind the attack.[320] Some Copts accused the Egyptian government of negligence,[321] and following the attacks many Christians protested in the streets, with Muslims later joining the protests. After clashing with the police, protesters in Alexandria and Cairo shouted slogans denouncing Mubarak's rule[322][323][324] in support of unity of Christians and Muslims. Their sense of being let down by national security forces has been cited as one of the first signs of the 25 January uprising.[325] On 7 February, a complaint was filed against Habib al-Adly, the Interior Minister until Mubarak's dissolution of the government during the early days of the protests, accusing him of having directed the attack.[326]

Women's role[edit]

Egyptian women were active throughout the revolution. Some took part in the protests themselves, were present in news clips and on Facebook forums, and were part of the leadership during the Egyptian revolution. In Tahrir Square, female protesters, some with their children, worked to support the protests. The diversity of the protesters in Tahrir Square was visible in the women who participated; many wore head scarves and other signs of religious conservatism, while others reveled in the freedom to kiss a friend or smoke a cigarette in public. Egyptian women also organised protests, and reported on the events; female bloggers such as Leil Zahra Mortada risked abuse or imprisonment by keeping the world informed of the daily scene in Tahrir Square and elsewhere.[328] Among those who died was Sally Zahran, who was beaten to death during one of the demonstrations. NASA reportedly plans to name one of its Mars exploration spacecraft in Zahran's honour.[329]

The wide participation and the significant contributions by Egyptian women to the protests were attributed to the fact that many, especially younger women, were better educated than previous generations, representing more than half of Egyptian university students. This was an empowering factor for women, who have become more present and active publicly in recent years, like Mae Zein ElDeen. The advent of social media also helped provide tools for women to become protest leaders.[328]

The military's role[edit]

The Egyptian Armed Forces initially enjoyed a better reputation with the public than the police does, the former perceived as a professional body protecting the country, the latter accused of systemic corruption and illegitimate violence. However, after the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces became the defacto ruler of Egypt, the popularity of the military has strongly decreased due to the crackdown on protesters. All four Egyptian presidents since the 1950s have come from the military into power. Key Egyptian military personnel include the Defense Minister Mohamed Hussein Tantawi and General Sami Hafez Enan, Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces.[330][331] The Egyptian military totals around 468,500 well-armed active personnel, plus a reserve of 479,000.[332]

As Head of Egypt's Armed Forces, Tantawi has been described as "aged and change-resistant" and is attached to the old regime. He has used his position as Defense Minister to oppose reforms, economic and political, which he saw as weakening central government authority. Other key figures, Sami Enan chief among them, are younger and have closer connections to both the US and groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood. An important aspect of the relationship between the Egyptian and American military establishments is the 1.3 billion dollars in military aid provided to Egypt annually, which in turn pays for American-made military equipment, and allows Egyptian officers to receive training in the US. Guaranteed this aid package, the governing military council is for the most reform-resistant.[333][334] One analyst however, while conceding that the military is change-resistant, states it has no option but to facilitate the process of democratisation. Furthermore, the military will have to keep its role in politics limited to continue good relations with the West, and must not restrict the participation of political Islam if there is to be a genuine democracy.[317]

The military has led a violent crackdown on the Egyptian revolution since the fall of Mubarak. On 9 March 2011, military police violently dispersed a sit-in in Tahrir square and detained protesters who were later moved to the Egyptian Museum and tortured.[335] Seven female protesters were subjected by force to virginity tests.[335] On the night of the 8 April 2011, military police attacked a sit-in in Tahrir square where protesters stayed overnight with military officers who joined the revolution, killing at least 1.[336] On 9 October, the Egyptian military forces committed massacres in front of Maspero, Egyptian state television buildling, where they crushed protesters under the wheels of armed personnel carriers, and shot live ammunition at the demonstration, killing at least 24 people.[337] On 19 November 2011, the military and the police were in a continuous 6-day battle with protestors in the streets of downtown Cairo and Alexandria. The bloody week resulted in at least 46 dead and thousands of injured, many of them lost their eyesight.[338] On 16 December 2011, military forces dispersed the sit-in at the Cabinet of Ministers, violently killing 17 protesters.[339] Aside from the live ammunition fired by military forces, military soldiers were situated on the rooftop of the Cabinet of Ministers building attacking protestors with Molotov cocktails, rocks, chinaware, granite, and other various objects.[340]

Foreign relations[edit]

Foreign governments in the West including the US have regarded Mubarak as an important ally and supporter in the Israeli-Palestinian peace negotiations.[45] After wars with Israel in 1948, '56, '67 and '73, Egypt signed a peace treaty in 1979, provoking controversy in the Arab world. As provisioned in the 1978 Camp David Accords, which led to the peace treaty, both Israel and Egypt receive billions of dollars in aid annually from the United States, with Egypt receiving over US$1.3 billion of military aid each year in addition to economic and development assistance.[341] According to Juan Cole, many Egyptian youth felt ignored by Mubarak on the grounds that he was not looking out for their best interests and that he rather served the interests of the West.[342] The cooperation of the Egyptian regime in enforcing the blockade of the Gaza Strip was also deeply unpopular among the general Egyptian public.[343]

Online activism and the role of social media[edit]

The 6 April Youth Movement (Arabic: حركة شباب 6 أبريل) is an Egyptian Facebook group started in Spring 2008 to support the workers in El-Mahalla El-Kubra, an industrial town, who were planning to strike on 6 April. Activists called on participants to wear black and stay home on the day of the strike. Bloggers and citizen journalists used Facebook, Twitter, Flickr, blogs and other new media tools to report on the strike, alert their networks about police activity, organize legal protection and draw attention to their efforts. The New York Times has identified the movement as the political Facebook group in Egypt with the most dynamic debates. As of March 2012, it had 325,000[344] predominantly young and educated members, most of whom had not been politically active before; their core concerns include free speech, nepotism in government and the country's stagnant economy. Their discussion forum on Facebook features intense and heated discussions, and is constantly updated with new postings.