'My Lobotomy': Howard Dully's Journey

Howard Dully during his transorbital lobotomy, Dec. 16, 1960.

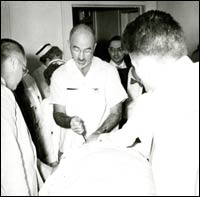

Howard Dully holding one of Dr. Walter Freeman's original ice picks, January 2004.

More About the Story

More From Sound Portraits

Additional interviews, oral histories and information about the documentary:

Excerpts from the Story

Dr. Walter Freeman operating on a patient, c. 1950.

Howard, standing in front, with his parents, June Dully and Rodney Dully (holding Howard's brother Brian), in Oakland, Calif., c. 1950.

Howard Dully's stepmother, Lou, in California, 1955.

Howard Dully, tree climbing in Los Altos, Calif., 1955.

Oral Histories

Patricia Moen was lobotomized by Walter Freeman in 1962 at the age of 36. As a staff physician at Ohio, Wolfhard Baumgartel observed Freeman perform a series of lobotomies.

On Jan. 17, 1946, a psychiatrist named Walter Freeman launched a radical new era in the treatment of mental illness in this country. On that day, he performed the first-ever transorbital or "ice-pick" lobotomy in his Washington, D.C., office. Freeman believed that mental illness was related to overactive emotions, and that by cutting the brain he cut away these feelings.

Freeman, equal parts physician and showman, became a barnstorming crusader for the procedure. Before his death in 1972, he performed transorbital lobotomies on some 2,500 patients in 23 states.

One of Freeman's youngest patients is today a 56-year-old bus driver living in California. Over the past two years, Howard Dully has embarked on a quest to discover the story behind the procedure he received as a 12-year-old boy.

In researching his story, Dully visited Freeman's son; relatives of patients who underwent the procedure; the archive where Freeman's papers are stored; and Dully's own father, to whom he had never spoken about the lobotomy.

"If you saw me you'd never know I'd had a lobotomy," Dully says. "The only thing you'd notice is that I'm very tall and weigh about 350 pounds. But I've always felt different -- wondered if something's missing from my soul. I have no memory of the operation, and never had the courage to ask my family about it. So two years ago I set out on a journey to learn everything I could about my lobotomy."

Neurologist Egas Moniz performed the first brain surgery to treat mental illness in Portugal in 1935. The procedure, which Moniz called a "leucotomy," involved drilling holes in the patient's skull to get to the brain. Freeman brought the operation to America and gave it a new name: the lobotomy. Freeman and his surgeon partner James Watts performed the first American lobotomy in 1936. Freeman and his lobotomy became famous. But soon he grew impatient.

"My father decided that there must be a better way," says Freeman's son, Frank. Walter Freeman set out to create a new procedure, one that didn't require drilling holes in the head: the transorbital lobotomy. Freeman was convinced that his 10-minute lobotomy was destined to revolutionize medicine. He spent the rest of his life trying to prove his point.

As those who watched the procedure described it, a patient would be rendered unconscious by electroshock. Freeman would then take a sharp ice pick-like instrument, insert it above the patient's eyeball through the orbit of the eye, into the frontal lobes of the brain, moving the instrument back and forth. Then he would do the same thing on the other side of the face.

Freeman performed the procedure for the first time in his Washington, D.C., office on Jan. 17, 1946. His patient was a housewife named Ellen Ionesco. Her daughter, Angelene Forester, was there that day.

"She was absolutely violently suicidal beforehand," Forester says of her mother. "After the transorbital lobotomy there was nothing. It stopped immediately. It was just peace. I don't know how to explain it to you, it was like turning a coin over. That quick. So whatever he did, he did something right."

Ellen Ionesco, now 88 years old, lives in a nursing home in Virginia. "He was just a great man. That's all I can say," she says. But Ionesco says she remembers little about Freeman, including what he looked like.

By 1949, the transorbital lobotomy had caught on. Freeman lobotomized patients in mental institutions across the country.

"There were some very unpleasant results, very tragic results and some excellent results and a lot in between," says Dr. Elliot Valenstein, who wrote Great and Desperate Cures, a book about the history of lobotomies.

Valenstein says the procedure "spread like wildfire" because alternative treatments were scarce. "There was no other way of treating people who were seriously mentally ill," he says. "The drugs weren't introduced until the mid-1950s in the United States, and psychiatric institutions were overcrowded... [Patients and their families] were willing to try almost anything."

By 1950, Freeman's lobotomy revolution was in full swing. Newspapers described it as easier than curing a toothache. Freeman was a showman and liked to shock his audience of doctors and nurses by performing two-handed lobotomies: hammering ice picks into both eyes at once. In 1952, he performed 228 lobotomies in a two-week period in West Virginia alone. (He lobotomized 25 women in a single day.) He decided that his 10-minute lobotomy could be used on others besides the incurably mentally ill.

Anna Ruth Channels suffered from severe headaches and was referred to Freeman in 1950. He prescribed a transorbital lobotomy. The procedure cured Channels of her headaches, but it left her with the mind of a child, according to her daughter, Carol Noelle. "Just as Freeman promised, she didn't worry," Noelle says. "She had no concept of social graces. If someone was having a gathering at their home, she had no problem with going in to their house and taking a seat, too."

Howard Dully's mother died of cancer when he was 5. His father remarried and, Dully says, "My stepmother hated me. I never understood why, but it was clear she'd do anything to get rid of me."

A search of Dully's records among Freeman's files archived at George Washington University turned up clues about why Freeman lobotomized him.

According to Freeman's notes, Lou Dully said she feared her stepson, whom she described as defiant and savage looking. "He doesn't react either to love or to punishment," the notes say of Howard Dully. "He objects to going to bed but then sleeps well. He does a good deal of daydreaming and when asked about it he says 'I don't know.' He turns the room's lights on when there is broad sunlight outside."

On Nov. 30, 1960, Freeman wrote: "Mrs. Dully came in for a talk about Howard. Things have gotten much worse and she can barely endure it. I explained to Mrs. Dully that the family should consider the possibility of changing Howard's personality by means of transorbital lobotomy. Mrs. Dully said it was up to her husband, that I would have to talk with him and make it stick."

Then on Dec. 3, 1960: "Mr. and Mrs. Dully have apparently decided to have Howard operated on. I suggested [they] not tell Howard anything about it."

In an entry dated Jan. 4, 1961, two and a half weeks after the boy's lobotomy, Freeman wrote: "I told Howard what I'd done to him... and he took it without a quiver. He sits quietly, grinning most of the time and offering nothing."

Dully says that when Lou Dully realized the operation didn't turn him "into a vegetable, she got me out of the house. I was made a ward of the state.

"It took me years to get my life together. Through it all I've been haunted by questions: 'Did I do something to deserve this?, Can I ever be normal?', and most of all, 'Why did my dad let this happen?'"

For more than 40 years, Howard Dully had never discussed the lobotomy with his father. In late 2004, Rodney Dully agreed to talk with his son about the operation.

"So how did you find Dr. Freeman?" Howard Dully asks.

"I didn't," Rodney Dully replies, adding that Lou Dully was the one. "She took you... I think she tried some other doctors who said, '...there's nothing wrong here. He's a normal boy.' It was the stepmother problem."

Why would a father let this happen to his son?

"I got manipulated, pure and simple," Rodney Dully says. "I was sold a bill of goods. She sold me and Freeman sold me. And I didn't like it."

The meeting proves cathartic for Howard Dully. "Although he refuses to take any responsibility, just sitting here with my dad and getting to ask him about my lobotomy is the happiest moment of my life," Howard Dully says.

Rebecca Welch's mother Anita was lobotomized by Freeman for postpartum depression in 1953. After spending most of her life in mental institutions, Anita McGee now lives in a nursing home in Birmingham, Ala. Rebecca visits her every week. She believes Walter Freeman's lobotomy destroyed her mother's life.

"I personally think that something in Dr. Freeman wanted to be able to conquer people and take away who they were," Welch says.

At a meeting in the nursing home, Welch and Howard Dully find common ground in their experiences with Freeman. "It does wonders to know that other people have the same pain," Dully says.

Howard Dully's two-year journey in search of the story behind his lobotomy is over. "I'll never know what I lost in those 10 minutes with Dr. Freeman and his ice pick," Dully says. "By some miracle it didn't turn me into a zombie, crush my spirit or kill me. But it did affect me. Deeply. Walter Freeman's operation was supposed to relieve suffering. In my case it did just the opposite. Ever since my lobotomy I've felt like a freak, ashamed."

But now, after meeting with Welch and her mother, Dully says his suffering is over. "I know my lobotomy didn't touch my soul. For the first time I feel no shame. I am, at last, at peace."

After 2,500 operations, Freeman performed his final ice-pick lobotomy on a housewife named Helen Mortenson in February 1967. She died of a brain hemorrhage, and Freeman's career was finally over. Freeman sold his home and spent the rest of his days traveling the country in a camper, visiting old patients, trying desperately to prove that his procedure had transformed thousands of lives for the better. Freeman died of cancer in 1972.

Saving Highlight

Saving Highlight

Saving Hilight for you...

Saving Hilight for you...

Un-highlight

Un-highlight

Comments

Discussions for this story are now closed. Please see the Community FAQ for more information.