The Song of Roland

| This is the current revision of this page, as edited by Yobot (talk | contribs) at 07:55, 12 October 2012. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this version. |

|

|

This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. (August 2012) |

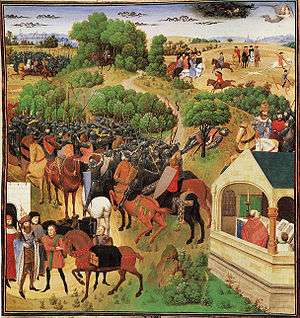

The Song of Roland (French: La Chanson de Roland) is a heroic poem based on the Battle of Roncesvalles in 778, during the reign of Charlemagne. It is the oldest surviving major work of French literature. It exists in various manuscript versions which testify to its enormous and enduring popularity in the 12th to 14th centuries. The oldest of these is the Oxford manuscript which contains a text of some 4,004 lines (the number varies slightly in different modern editions) and is usually dated to the middle of the twelfth century (between 1140 and 1170). The epic poem is the first and most outstanding example of the chanson de geste, a literary form that flourished between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries and celebrated the legendary deeds of a hero.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Manuscripts

There are nine extant manuscripts of the Song of Roland in Old French. The oldest of these manuscripts is held at the Bodleian Library at Oxford. This copy dates between 1140 and 1170 and was written in Anglo-Norman.[1]

Scholars estimate that the poem was written between approximately 1040 and 1115, and most of the alterations were performed by about 1098. Some favor an earlier dating, because it allows one to say that the poem was inspired by the Castilian campaigns of the 1030s, and that the poem went on to be a major influence in the First Crusade. Those who prefer a later dating do so on grounds of the brief references made in the poem to events of the First Crusade. In one section, Palestine is named Outremer, its Crusader name – but is presented as a Muslim land where there are no Christians.

[edit] Critical opinions

[edit] Oral performance of the Song compared to manuscript versions

Scholarly consensus has long accepted that the Song of Roland differed in its presentation depending on oral or textual transmission; namely, although a number of different versions of the song containing varying material and episodes would have been performed orally, the transmission to manuscript resulted in greater cohesiveness across versions.

Early editors of the Song of Roland, informed in part by patriotic desires to produce a distinctly French epic, could thus overstate the textual cohesiveness of the Roland tradition. This point is clearly expressed by Andrew Taylor, who notes.[2] "[T]he Roland song was, if not invented, at the very least constructed. By supplying it with an appropriate epic title, isolating it from its original codicological context, and providing a general history of minstrel performance in which its pure origin could be located, the early editors presented a 4,002 line poem as sung French epic".

[edit] Plot

Charlemagne's army is fighting the Muslims in Spain. The last city standing is Saragossa, held by the Muslim king Marsilla. Terrified of the might of Charlemagne's army of Franks, Marsilla sends out messengers to Charlemagne, promising treasure and Marsilla's conversion to Christianity if the Franks will go back to France. Charlemagne and his men are tired of fighting and decide to accept this peace offer. They need now to select a messenger to go back to Marsilla's court.

The bold warrior Roland nominates his stepfather Ganelon. Ganelon is enraged; he fears that he'll die in the hands of the bloodthirsty pagans and suspects that this is just Roland's intent. He has long hated and envied his stepson, and, riding back to Saragossa with the Saracen messengers, he finds an opportunity for revenge. He tells the Saracens how they could ambush the rear guard of Charlemagne's army, which will surely be led by Roland as the Franks pick their way back to Spain through the mountain passes, and helps the Saracens plan their attack.

Just as the traitor Ganelon predicted, Roland gallantly volunteers to lead the rear guard. The wise and moderate Oliver and the fierce Archbishop Turpin are among the men Roland picks to join him. Pagans ambush them at Roncesvalles, according to plan; the Christians are overwhelmed by their sheer numbers. Seeing how badly outnumbered they are, Olivier asks Roland to blow on his olifant, his horn made out of an elephant tusk, to call for help from the main body of the Frankish army. Roland proudly refuses to do so, claiming that they need no help, that the rear guard can easily take on the pagan hordes.

While the Franks fight magnificently, there's no way they can continue to hold off against the Saracens, and the battle begins to turn clearly against them. Almost all his men are dead and Roland knows that it's now too late for Charlemagne and his troops to save them, but he blows his oliphant anyway, so that the emperor can see what happened to his men and avenge them. Roland blows so hard that his temples burst. He dies a glorious martyr's death, and saints take his soul straight to Paradise.

When Charlemagne and his men reach the battlefield, they find only dead bodies. The pagans have fled, but the Franks pursue them, chasing them into the river Ebro, where they all drown.

Meanwhile, the powerful emir of Babylon, Baligant, has arrived in Spain to help his vassal Marsilla fend off the Frankish threat. Baligant and his enormous Muslim army ride after Charlemagne and his Christian army, meeting them on the battlefield at Roncesvalles, where the Christians are burying and mourning their dead. Both sides fight valiantly. But when Charlemagne kills Baligant, all the pagan army scatter and flee.

Now Saragossa has no defenders left; the Franks take the city. With Marsilla's wife Bramimonde, Charlemagne and his men ride back to Aix, their capital in France.

The Franks discovered Ganelon's betrayal some time ago and keep him in chains until it is time for his trial. Ganelon argues that his action was legitimate revenge, openly proclaimed, not treason. While the council of barons which Charlemagne has assembled to decide the traitor's fate is initially swayed by this claim, one man, Thierry, argues that, because Roland was serving Charlemagne when Ganelon delivered his revenge on him, Ganelon's action constitutes a betrayal of the emperor.

Ganelon's friend Pinabel challenges Thierry to trial by combat; the two will fight a duel to see who's right. By divine intervention, Thierry, the weaker man, wins, killing Pinabel. The Franks are convinced by this of Ganelon's villainy and sentence him to a most painful death. The traitor is torn limb from limb by galloping horses and thirty of his relatives are hung for good measure.

[edit] Form

The poem is written in stanzas of irregular length known as laisses. The lines are decasyllabic (containing ten syllables), and each is divided by a strong caesura which generally falls after the fourth syllable. The last stressed syllable of each line in a laisse has the same vowel sound as every other end-syllable in that laisse. The laisse is therefore an assonal, not a rhyming stanza.

On a narrative level, the Song of Roland features extensive use of repetition, parallelism, and thesis-antithesis pairs. Unlike later Renaissance and Romantic literature, the poem focuses on action rather than introspection.

The author gives few explanations for characters' behavior. The warriors are stereotypes defined by a few salient traits; for example, Roland is loyal and trusting while Ganelon, though brave, is traitorous and vindictive.

The story moves at a fast pace, occasionally slowing down and recounting the same scene up to three times but focusing on different details or taking a different perspective each time. The effect is similar to a film sequence shot at different angles so that new and more important details come to light with each shot.

[edit] Characters

[edit] Principal characters

- Baligant, emir of Babylon; Marsile enlists his help against Charlemagne.

- Blancandrin, wise pagan; suggests bribing Charlemagne out of Spain with hostages and gifts, and then suggests dishonouring a promise to allow Marsile's baptism

- Bramimonde, Queen of Saragossa; captured and converted by Charlemagne after the city falls

- Charlemagne, Holy Roman Emperor; his forces fight the Saracens in Spain.

- Ganelon, treacherous lord and Roland's stepfather who encourages Marsile to attack the French

- King Marsile, Saracen king of Spain; Roland wounds him and he dies of his wound later.

- Naimon, Charlemagne's trusted adviser.

- Olivier, Roland's friend; mortally wounded by Margarice. He represents wisdom.

- Roland, the hero of the Song; nephew of Charlemagne; leads the rear guard of the French forces; bursts his temples by blowing his oliphant-horn, wounds from which he eventually dies facing the enemy's land.

- Turpin, Archbishop of Rheims, represents the force of the Church.

[edit] Secondary characters

- Aude, the fiancée of Roland and Olivier's sister

- Basan, French baron, murdered while serving as Ambassador of Marsile.

- Bérengier, one of the twelve paladins killed by Marsile’s troops; kills Estramarin; killed by Grandoyne.

- Besgun, chief cook of Charlemagne's army; guards Ganelon after Ganelon's treachery is discovered.

- Geboin, guards the French dead; becomes leader of Charlemagne's 2nd column.

- Godefroy, standard bearer of Charlemagne; brother of Thierry, Charlemagne’s defender against Pinabel.

- Grandoyne, fighter on Marsile’s side; son of the Cappadocian King Capuel; kills Gerin, Gerier, Berenger, Guy St. Antoine, and Duke Astorge; killed by Roland.

- Hamon, joint Commander of Charlemagne's Eighth Division.

- Lorant, French commander of one of the of first divisions against Baligant; killed by Baligant.

- Milon, guards the French dead while Charlemagne pursues the Saracen forces.

- Ogier, a Dane who leads the third column in Charlemagne's army against Baligant's forces.

- Othon, guards the French dead while Charlemagne pursues the Saracen forces.

- Pinabel, fights for Ganelon in the judicial combat.

- Thierry, fights for Charlemagne in the judicial combat.

[edit] Adaptations

A Latin poem, Carmen de Prodicione Guenonis, was composed around 1120, and a Latin prose version, Historia Caroli Magni (often known as "The Pseudo-Turpin") even earlier. Around 1170, a version of the French poem was translated into the Middle High German Rolandslied by Konrad der Pfaffe (possible author also of the Kaiserchronik). In his translation Konrad replaces French topics with generically Christian ones. The work was translated into Middle Dutch in the 13th century. It was also rendered into Occitan verse in the 14th or 15th century poem of Ronsasvals, which incorporates the later, southern aesthetic into the story. An Old Norse version of the Song of Roland exists as Karlamagnús saga, and a translation into the artificial literary language of Franco-Venetian is also known; such translations contributed to the awareness of the story in Italy. In 1516 Ludovico Ariosto published his epic Orlando Furioso, which deals largely with characters first described in the Song of Roland.

There is also Faroese adoption of this ballad named "Runtsivalstríðið"(Battle of Roncevaux). The ballad is one of many sung during the Faroese folkdance tradition of chain dancing.

[edit] Modern adaptations

The English progressive rock band Van der Graaf Generator recorded a song, "Roncevaux", that tells the famous story. Norwegian folk metal band Glittertind[3] and Norwegian polyphonic vocal group Trio Mediæval both recorded versions of "Rolandskvadet," based on part of "The Song of Roland." The Norwegian singer Erik Bye has also made a musical interpretation called "Rolandskvadet". The French black metal band Peste Noire used a fragment of the Song of Roland as lyrics for their song 'La Fin del Secle'. The Warren Zevon song "Roland the Headless Thompson Gunner" includes parallels with "The Song of Roland." In Zevon's song, the eponymous Roland has his head blown off by one of his fellow mercanaries, named Van Owen (a name resembling the trisyllable pronunciation of Ganelon). In addition, both Van Owen and Ganelon meet bloody reprisals for their deeds. Van Owen's body is blown from "here to Johannesburg" by a decapitated Roland while Ganelon is torn in pieces for being a traitor to Charlemagne's army.

The Italian composer Luigi Dallapiccola set "Rencesvals: Trois Fragments de la Chanson de Roland" for mezzo-soprano and piano in 1946. It was dedicated "à mes amis Pierre Bernac et Francis Poulenc," the leading performers of French art song at the time, and is typical of Dallapiccola's usage of the 12-tone style of composition.

The Chanson de Roland has an important place in the background of Graham Greene's The Confidential Agent. The book's protagonist had been a Medieval scholar specialising in this work, until the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War forced him to become a soldier and secret agent. Throughout the book, he repeatedly compares himself and other characters with the characters of "Roland". Particularly, the book includes a full two pages of specific commentary, which is relevant to its 20th Century plotline: "Oliver, when he saw the Saracens coming, urged Roland to blow his horn and fetch back Charlemagne - but Roland wouldn't blow. A big brave fool. In war one always chooses the wrong hero. Oliver should have been the hero of that song, instead of being given second place with the blood-thirsty Bishop Turpin.(...) In the Oxford version Oliver is reconciled in the end, he gives Roland his death-blow by accident, his eyes blinded by wounds. [But] the story had been tidied up. In truth, Oliver strikes his friend down in full knowledge - because of what he has done to his men, all the wasted lives. Oliver dies hating the man he loves - the big boasting courageous fool who was more concerned with his own glory than with the victory of his faith. This makes the story tragedy, not just heroics".[4]

[edit] See also

[edit] Notes

- ^ Ian, Short (1990). "Introduction". La Chanson de Roland. France: Le Livre de Poche. pp. 5–20.

- ^ Taylor, Andrew, "Was There a Song of Roland?" Speculum 76 (January 2001): 28-65

- ^ "Glittertind - Rolandskvadet (live)". YouTube. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9ErNXdtNRPI. Retrieved 2012-04-21.

- ^ "The Confidential Agent", Part 1, Ch. 2, quoted in "Graham Greene: an approach to the novels" by Robert Hoskins, p. 122 [1]

[edit] External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: The Song of Roland |

| French Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- The Song of Roland at Project Gutenberg (English translation of Charles Kenneth Scott Moncrieff)

- The Digby 23 Project at Baylor University

- The Song of Roland

- La Chanson de Roland (Old French)

- The Romance of the Middle Ages: The Song of Roland, discussion of Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Digby 23, audio clip, and discussion of the manuscript's provenance.

- Earliest manuscript of the Chanson de Roland, readable online images of the complete original, Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Digby 23 (Pt 2) "La Chanson de Roland, in Anglo-Norman, 12th century, ? 2nd quarter".

- Old French Audio clips of a reading of The Song of Roland in Old French

- Timeless Myths: Song of Roland

"The Song of Roland". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

"The Song of Roland". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

|

||||||||||||||||||||