Beauty and the Beast (1946 film)

|

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2009) |

| Beauty and the Beast | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Directed by | Jean Cocteau |

| Produced by | André Paulvé |

| Screenplay by | Jean Cocteau |

| Based on | Beauty and the Beast by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont |

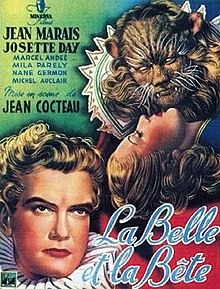

| Starring | Jean Marais Josette Day Mila Parély Nane Germon Michel Auclair Marcel André |

| Music by | Georges Auric |

| Cinematography | Henri Alekan |

| Editing by | Claude Iberia |

| Distributed by | Lopert Pictures |

| Release date(s) |

|

| Running time | 93 min. |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

Beauty and the Beast (French: La Belle et la Bête) is a 1946 French romantic fantasy film adaptation of the traditional fairy tale of the same name, written by Jeanne-Marie Le Prince de Beaumont and published in 1757 as part of a fairy tale anthology (Le Magasin des Enfants, ou Dialogues entre une sage gouvernante et ses élèves, London 1757). Directed by French poet and filmmaker Jean Cocteau, the film stars Josette Day as Belle and Jean Marais.

The plot of Cocteau's film revolves around Belle's father who is sentenced to death for picking a rose from Beast's garden. Belle offers to go back to the Beast in her father's place. Beast falls in love with her and proposes marriage on a nightly basis which she refuses. Belle eventually becomes more drawn to Beast, who tests her by letting her return home to her family and telling her that if she doesn't return to him within a week, he will die of grief.

Contents[hide] |

Plot summary [edit]

While scrubbing the floor at home, Belle (Josette Day) is interrupted by her brother's friend Avenant (Jean Marais) who tells her she deserves better and suggests they get married. Belle rejects Avenant, as she wishes to stay home and take care of her father, who has suffered much since his ships were lost at sea and the family fortune along with them. Belle's father (Marcel André) arrives home announcing he has come into great fortune that he will pick up the next day, along with gifts for his daughters, Belle's shrewish sisters Adelaide and Felicie. Belle's roguish brother Ludovic (Michel Auclair) signs a contract from a moneylender (Raoul Marco) allowing him to the ability to sue Ludovic's father if he can't pay. Later, Belle's father finds on his arrival that his fortune has been seized to clear his debts and is forced to return home through the forest at night.

Belle's father gets lost in the forest and finds himself at a large castle whose gates and doors magically open themselves. On entering the castle, he is guided by an enchanted candelabra that leads him to a laden dinner table where he falls asleep. Awakened by a loud roar, Belle's father wanders the castle's grounds. Remembering that Belle asked for a rose, he plucks a rose from a tree which makes the Beast (Jean Marais) appear. The Beast threatens to kill him for theft but then suggests that one of his daughters can take his place. The Beast offers his horse Magnificent to guide him through the woods home. Belle's father explains the situation to his family and Avenant, as Belle agrees to go and take her father's place. Belle rides Magnificent to the castle, finding the Beast. Belle faints at the sight of him and is carried to her room in the castle. Belle wakes up and finds a magic mirror which allows her to see anything. The Beast invites Belle to dinner, where he tells her that she's in equal command to him and that she will be asked every day to marry him. Days pass as Belle grows more accustomed and fond of the Beast, but continues to refuse marriage. Using the magic mirror Belle finds her father deathly ill. The Beast grants her permission to leave for a week. He gives Belle two magical items: A glove that can transport her wherever she wishes and a golden key that unlocks Diana's Pavilion, the source of the Beast's true riches.

Belle uses the glove to appear in her bedridden father's room, where her visit restores him to health. Belle finds her family living in poverty, having never recovered from Ludovic's deal with the moneylender. Jealous of Belle's rich life at the castle, Adelaide and Felicie steal her golden key and devise a plan to turn Ludovic and Avenant against the Beast. Avenant and Ludovic devise a plan of their own to kill the Beast, and agree to aid Belle's sisters. To stall Belle, her sisters trick her into staying past her seven day limit by pretending to love her. Belle reluctantly agrees to stay. The Beast sends Magnificent with the magic mirror to retrieve Belle but Ludovic and Avenant find Magnificent first, and ride him to the castle. Belle later finds the mirror which reveals the Beast's sorrowful face in its reflection. Belle realizes she is missing the golden key as the mirror breaks. Distraught, Belle returns to the castle using the magic glove and finds the Beast in the courtyard, near death from a broken heart. Meanwhile, Avenant and Ludovic stumble upon Diana's Pavilion. Thinking that their stolen key may trigger a trap, they scale the wall of the Pavilion. As the Beast dies in Belle's arms, Avenant breaks into the Pavilion through its glass roof and is shot with an arrow by an animated statue of the Roman goddess Diana and is himself turned into a Beast. As this happens, arising from where the Beast lay dead is Prince Ardent (Jean Marais) who is cured from being the Beast. Prince Ardent and Belle embrace, then fly away to his kingdom where she will be his Queen, and where her father will stay with them and Belle's sisters will carry the train of her gown.

Cast [edit]

- Jean Marais — La Bête (The Beast) / The Prince / Avenant

- Josette Day — Belle

- Mila Parély — Félicie

- Nane Germon — Adélaïde

- Michel Auclair — Ludovic

- Raoul Marco — The Usurer

- Marcel André — Belle's Father

Preamble [edit]

After the opening credits, Cocteau briefly breaks the fourth wall with a written preamble:[1]

|

|

Production [edit]

The score was composed by Georges Auric, and the cinematography by Henri Alekan. Christian Bérard and Lucien Carré covered production design. As mentioned in the DVD extras the exteriors were shot in the Château de la Roche Courbon (Indre-et-Loire).

The set designs and cinematography were intended to evoke the illustrations and engravings of Gustave Doré and, in the farmhouse scenes, the paintings of Jan Vermeer.

Reception [edit]

Upon the film's December 1947 New York City release, critic Bosley Crowther called the film a "priceless fabric of subtle images,...a fabric of gorgeous visual metaphors, of undulating movements and rhythmic pace, of hypnotic sounds and music, of casually congealing ideas"; according to Crowther, "the dialogue, in French, is spare and simple, with the story largely told in pantomime, and the music of Georges Auric accompanies the dreamy, fitful moods. The settings are likewise expressive, many of the exteriors having been filmed for rare architectural vignettes at Raray, one of the most beautiful palaces and parks in all France. And the costumes, too, by Christian Bérard and Escoffier, are exquisite affairs, glittering and imaginative."[2] According to Time magazine, the film is a "wondrous spectacle for children of any language, and quite a treat for their parents, too"; but the magazine concludes "Cocteau makes about a half-hour too much of a good thing—and few things pall like a dream that cannot be shaken off."[3]

In 1999, Chicago Sun-Times critic Roger Ebert added the film to his "Great Movies" list, calling it "one of the most magical of all films" and a "fantasy alive with trick shots and astonishing effects, giving us a Beast who is lonely like a man and misunderstood like an animal."[4] A 2002 Village Voice review found the film's "visual opulence" "both appealing and problematic", saying "Full of baroque interiors, elegant costumes, and overwrought jewelry (even tears turn to diamonds), the film is all surface, and undermines its own don't-trust-a-pretty-face and anti-greed themes at every turn."[5] In 2010, the film was ranked #26 in Empire magazine's "100 Best Films of World Cinema".[6]

Related works [edit]

Departures from original tale [edit]

|

|

This section may contain original research. (October 2011) |

This film adaptation of La Belle et la Bete adds a subplot involving Belle's suitor Avenant, who schemes along with Belle's brother and sisters to journey to Beast's castle to kill him and capture his riches while the sisters work to delay Belle's return to the castle. When Avenant enters the magic pavilion which is the source of Beast's power, he is struck by an arrow fired by a guardian statue of the Roman goddess Diana, which transforms Avenant into Beast as Belle declares her love for the Beast and reverses the original Beast's curse. When the Beast comes back to life and becomes human at the end, he transforms into a Prince Charming with Avenant's handsome features, but without his oafish personality.

The adaptation also borrows from La Chatte Blanche by Marie-Cathérine d'Aulnoy, published in Les Contes des Fées, Paris 1697-1698, in which servants, previously magically reduced to their arms and hands, still perform all servants' chores.

In the original tale, Belle has three brothers, whereas in the film, she only has one. Also in the original tale, Belle and her family are forced to move to a farmstead in the countryside after the loss of their fortune; in the film, they continue to live in their townhouse. Also in the original tale, the sisters are turned into statues as punishment for their cruelty, whereas in the film, they are merely forced to carry the train of Belle's gown at her wedding, though it is implied that they will now be her servants.

In the fairytale, Belle repeatedly has dreams about the a handsome prince (the Beast in his true form) imploring her to love the Beast, to which she replies she cannot. She believes this Prince is, like herself, a captive in the Beast's castle and searches for him during the day. This does not occur in the film.

Jean Marais originally suggested to Cocteau for the beast to have a stag's head,[citation needed] obviously remembering a detail in the fairy tale (French: La Chatte blanche): The knocker at the gate to the castle of the princess/The White Cat has the form of a roe's foot. While this suggestion followed the narrative lines of its fairy tale origin and would have evoked the mythical echo of Cernunnos, the Celtic stag-headed god of the woods. Marais' idea was nonetheless refused by Cocteau who feared that in the eyes of modern cinema audiences a stag's head would turn the beast into a laughing-stock.

Adaptations and homages [edit]

- In 1994, composer Philip Glass created an opera version — also called La Belle et la Bête — one of a "Cocteau Trilogy" of operas. In its initial incarnation the musicians and singers would perform the work on stage with a restored, newly subtitled print of the film playing on a screen behind them. In the original presentation, Belle was sung by the mezzo-soprano Janice Felty. (The current Criterion Collection DVD and Blu-ray release offers the ability to view the movie while listening to either Glass's score or the original soundtrack.)

- American singer-songwriter Stevie Nicks wrote her 1983 ballad "Beauty and the Beast" after screening the film for the second time. While playing the song in concert, the film plays on the screen behind her and the band.

- The fourteenth episode of Faerie Tale Theatre featured an adaptation of Beauty And The Beast which was an homage to this film. It borrowed many visual elements, including the makeup for the beast, along with segments of the dialogue translated from French into English. It featured Susan Sarandon as Belle and Klaus Kinski as the Beast.

- The 2003 American miniseries Angels in America features a dream sequence which duplicates the set design of the Beast's castle. A character is shown reading a book about Cocteau before the dream begins.

References [edit]

|

|

This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. (October 2011) |

Specific references:

- ^ "La belle et la bête de Jean Cocteau". LaMaisonDesEnseignants.com (in French). LM2E. Retrieved 2011-10-24.; the English translation is from the Janus Films / Criterion Collection DVD

- ^ Bosley Crowther (December 24, 1947). "La Belle et la Bete (1946)". NYT Critics' Pick. The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ "Good & French". Time. December 29, 1947. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ Roger Ebert (December 26, 1999). "Beauty and the Beast (1946)". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ Michael Miller (August 13, 2002). "Simple Twists of Fate". Village Voice. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema". Empire. Text " 26. Beauty and the Beast " ignored (help)

General references:

- Marie-Cathérine d'Aulnoy, La Chatte blanche, in: Les Contes des Fées, Paris 1697-1698, reprinted in German in: Französische Märchen, Auswahl und Einleitung von Jack Zipes, Frankfurt/Main, Verlag Zweitausendeins, Lizenausgabe des Insel-Verlages, Mainz/Leipzig 1991, S. 123-156.

- Jeanne-Marie Le Prince de Beaumont, La Belle et la bête, in: Le Magasin des Enfants, ou Dialogues entre une sage gouvernante et ses élèves, London 1757, reprinted in German in: Französische Märchen, Auswahl und Einleitung von Jack Zipes, Frankfurt/Main, Verlag Zweitausendeins, Lizenausgabe des Insel-Verlages, Mainz/Leipzig 1991, S. 321-336.

External links [edit]

- Beauty and the Beast at the TCM Movie Database

- Beauty and the Beast at AllRovi

- Beauty and the Beast at the Internet Movie Database

- Beauty and the Beast at Metacritic

- Beauty and the Beast at Rotten Tomatoes

- Criterion Collection Essay by Geoffrey O’Brien

- Criterion Collection Essay by Francis Steegmuller

|

||||||||